An Interview with S. V. Medaris

by Benjamin Davis Brockman

by Benjamin Davis Brockman

October 1, 2012

S. V. (Sue) Medaris is a busy woman. She’s accomplished 10 solo gallery shows in just seven years, during which time she has worked as part-time as a web designer and illustrator, completed her Master’s degree in printmaking at UW Madison, and ran a farm with her husband in southwestern Wisconsin. She recently illustrated a book of essays on the wonders of living with chickens, Cluck: From Jungle Fowl to City Chicks. This is a subject on which Sue is an expert. I first met Sue at a workshop at North Carolina’s Penland School of craft, where I was assisting a mezzotint workshop. I knew nothing about Sue’s work until I discovered that we shared a penchant for oversized woodcuts. I was even more curious about her work after seeing the print she produced during that workshop—which was an immaculate dramatic portrait of a pair of chicken in mezzotint with chine-collé. Upon perusing the blog for her aptly named Market Weight Press, my intrigue grew as this world of farm animals proliferated. Large scale woodcut hogs, breathtaking paintings of farm dogs, rich relief portrayals of majestic chickens, painted taxidermy forms, and a myriad of applications function and contexts, in which the creatures came to life.

These images were interspersed with written narratives of her farm life, with titles such as “I skinned my first deer!” and “Alpaca gives birth”—making the world of her work tangible and real. At first glance, some of the images in the expansive catalog on her website could be dismissed as perfectly rendered illustrations, suitable for the homes of just about anybody with a soft spot for good ol’ Americana. However, the scope of this work is much deeper that any one of her works let on. Her recent installation piece, The Tunnel of Mortality, incorporated a number of visual media to depict the ins and outs of animal husbandry in very plain, unbiased language—from birth, through caretaking, to slaughter (i.e.: processing). As the phenomenon of the American farm gains attention, we all have to look very closely at where exactly our food comes from. However, very few of us eat food that comes directly out of our back yards. And this way of life has given Sue Medaris a stunning creative trajectory.

The Fiddleback: You recently illustrated a book. Do you find that there are constrictions in working to illustrate the ideas of others? Are there ways in which that is liberating?

S.V. Medaris: Actually, this was not the usual illustration job. The publisher first saw my work years ago at my first solo exhibit, A One Chick Show, in 2004. She approached me in 2010 saying she and her writer friend would like to do a book about chickens based on my artwork. The writer would write short essays about chickens, and my work would be on every page—sometimes corresponding to the work and sometimes not. I was in the middle of grad school, so my first question was “Do I have to make new artwork for this?” and she replied “not at all.” Turns out that I did some more chicken art that year in grad school, so we just added anything chicken related to the book (published in 2011). I was an illustrator from 1996 to 2003 and enjoyed it a lot, especially if I was being directed by a good art director. Then it was a blast. I still illustrate as my day job for The Why Files at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The Fiddleback: You have a degree in Commercial Art. How do you see the relationship between your commercial work and the stuff you do just for yourself?

SVM: The degree I earned at Madison Technical College changed my life. It was there that I learned how to design for the first time. Design is everything. It’s how you look at something, how you feel when you look at it, and it dictates where your eye goes within a specific hierarchy. Before this realizing this idea of design, I had just rendered things. I was always good at seeing and rendering, but this was totally different. Suddenly, through design, I could grab the viewers’ attention and direct them through the piece. If the action was about to tumble out of the frame, I could make the viewer feel like he/she was going to tumble out as well. It was at the Technical College that I also learned how to paint and use pastels. Soon after taking a semester of each, I was equipped to create the One Chick Show I mentioned.

Opening night, half the work sold. By end of show run, it was sold out. Within the next year, even the 20ft chicken mural sold. After opening night I realized I could make money selling fine art, and my husband (who was game as long as money could be made) gave me his blessing to stop illustrating and switch to fine art shows. I did have my half-time job for The Why Files, and we’ve always needed that financially—and that’s never stopped—but with a half-time job, I could still have time to do my own art.

Anyway, I made enough money from the chicken show to pay off credit card debts from frames, materials, etc, plus more importantly, I had enough leftover to do the 2nd solo show one year later, The Lives of Farm Dogs. And so forth: a solo show per year since then. I wouldn’t have been able to do what I do if I hadn’t learned about design at the Technical College. That started the whole return to Fine Art.

The Fiddleback: After you got your undergraduate degree from Santa Barbara, you traveled internationally for a while. There is such a familiar sense of home in many of your works, especially your paintings. Do your experiences abroad inform your interests?

SVM: I’ve only really travelled or spent time in Mexico and Central America. I wanted to have adventures after my relatively safe and calm life. One thing I noticed is that unlike my middle-class background (undergrad college life in Santa Barbara or life growing up in Madison), the world was very different from what I had previously thought of as the norm. There was poverty and suffering and people worked hard to survive. In the jungle, I relished the work, and working just to live: harvesting, shelling, cooking and grinding corn for tortillas, and cooking them over the fire. I had a baby–came back to the states for his birth, then went back to the jungle, washing clothes and diapers by hand with water hauled from the stream by horses during the dry season, or collected in buckets from rainwater off the roof of the Champa. I carried my baby in a sling while I worked around the homestead, went to the fields or walked the 12 miles to the nearest town, wielding a machete everywhere I went for chopping, cutting, killing snakes. This was not something I grew up with. For me it was an adventure. But for anyone growing up in this environment, it was just hard work from childhood on. I realized I had lived an extremely privileged life, and to this day I don’t forget it. I’m still thankful for washing machines, refrigerators and electricity. All of these time-saving devices that give me time to make artwork. In the jungle there is no time for artwork. There is no need for artwork. It takes all day of non-stop working just to subsist.

You bet that changed my life, outlook and work. I realized I love to work hard at everything I do. It’s why I live on this farm with my husband and raise animals for meat. It’s why if I’m not busy working on a next show or project, I feel very lazy and depressed. It’s why if I’m going to create a show, it better be something valid–it needs to teach or show something to the audience that they haven’t experienced before. I don’t want to just make pretty things, I need to tell a story or communicate an idea or create a scene or an experience in which you feel as if you’re there. I want to make the viewer smile or think or be amazed. I want drama. If the art isn’t going to do any of these things, then I have no reason to make it.

But perhaps the biggest reason for the work ethic is deadlines….I’m afraid if I didn’t schedule the solo shows and make those deadlines, I probably wouldn’t get much work done.

The Fiddleback: In a 2006 article you said of working from farm surroundings: “Sometimes, I feel like a photojournalist. I’m recording what this kind of life is like now, because I don’t know if it’s going to be here tomorrow.” In feeling that way, do you ever feel as though you have adopted that role? Has your artistic identity changed over the years?

SVM: I do like to document what happens here still. The difference is that the older I get the more I realize that I’m running out of time. I’m going to stop being on this earth before this sort of life stops existing. I think that’s the main reason to not slow down too much. It’s what drives me. Life is so quick. Yes, it’s cliché, but when I turned 40 I panicked that I hadn’t yet had a one-woman show since undergrad, and my life could very well be half-way over. That put me into overdrive, and I started on the One Chick Show soon after. You could change that quote above to …because I don’t know if I’M going to be here tomorrow. Living life to the fullest each day has become the goal for the past 10 years. Yes, I still need to document what I see and experience every day. It’s so dramatic, and you just don’t experience these things unless you live here. Photograph that beautifully fluffy fat hen for reference before a raccoon comes and drags her away…get that reference of my Great Pyrenees, Ivan, running across the hilltop before he gets too old to romp…photograph the freshly killed deer while you can still see the strength and beauty, before you skin it….capture the crazed look of anticipation before Dexter engulfs the live chick in his mouth. All of these priceless references for future block prints and paintings.

The Fiddleback: What specifically are your fears for the American farm? Do you think your work exemplifies or romanticizes that lifestyle in any way? Do you feel as though your work is overtly political, or are the politics merely implied by virtue of your subjects?

SVM: I think the politics are merely implied by the subjects, like you say. At this time in history, people do think about where their food comes from, especially while experts, writers and filmmakers, are trying to tell the public what is best. I try to simply show what’s going on here—the realities of farm life—because I deal with it on a daily basis. I don’t think that what I do is right or wrong, it’s just what I do because I live on a farm and I’m going to eat meat (I was a vegetarian for 10 years in my youth), so I might as well raise the animals I’m going to eat. Otherwise, I’d be in a store buying meat from an animal raised by other farmers. I don’t intentionally sentimentalize nor romanticize nor judge. I don’t want to tell people what to do or how to think. I want them to come at the artwork and look. If I’ve done my job, they stay and start thinking about it, try to figure out what it is, what’s being said, and how they feel about it. The Tunnel of Mortality installation, which was displayed this June through September, I think best exemplifies what I’m trying to do. I just put it out there to experience.

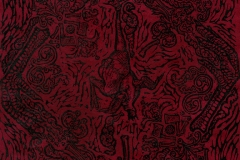

With The Tunnel, you walk into the anteroom, which looks elegant and Victorian and dark. The wallpaper is a linocut black print, repeated over 500 times on burgundy duck cloth. It looks beautiful and intricate, but if you look closer, there’s bones and chicken innards, and axes and chicken claws…death. The portraits around the anteroom are reduction woodcuts made to look like old Flemish paintings of royalty by the window. You’ll see a tom turkey, hen, polish chicken or hog, harshly, dramatically lit from the window—a royal portrait. But in the window scene, if you look close, it shows what is to come: the thanksgiving table, or the livestock boarding the trailer to the meat locker, or arriving at the butcher, or a huge possum about to enter the henhouse. Death is everywhere, but only if you look closely. Then you turn and see the big framed piece. It sort of moves–is it a mirror?– but no, you can put your hand through the picture plane, and then you see it’s a huge tunnel book, with happy scenes of farm life, pigs growing into hogs, and dogs playing. Then, further along, carcasses, and in the back, the butcher with a steer which he has slashed open. This whole experience is presented to the viewer so they can experience all the visuals of the farming process in raising animals for meat.

The best part of the show for me was reading the guestbook. I had invited visitors to write their thoughts. And in reading them, I quickly realized that the installation had worked! People actually came in and looked and thought about things: life, death, where our food comes from.

The Fiddleback: In the same article mentioned before, the author refers to your work as having an “overall lack of sentimentality.” How do you respond to that? If there is a journalistic side to your creative practice, do you think there is some type of responsibility inherent in portraying the world around you in a certain way?

I absolutely loved it when the journalist wrote that. I remember thinking: “She gets it! Yes!!” I don’t “do” cute. I don’t try to show sentiment. I try to show drama, yes, but by showing the reality of life out here. Things die all the time. That’s what struck me as being so different from my childhood growing up in the city. The death of things is so much more visible out here. Maybe because there’s just more of it: wildlife, livestock, and the interaction between the two. Well, and now I raise animals for meat. I kill my broiler chickens, pluck [and] process them, and I drive the turkeys and hogs to the meat locker to have them processed. If we catch a raccoon in the trap, it gets shot. The hogs that were frolicking in the pasture below just weeks ago are now in the freezer. So yeah, there’s more death out here in part because I cause it. I do try to show this reality of this death in the artwork, or sometimes just hint at it. Whenever I make a piece that’s dark or graphic, it usually doesn’t sell, but I put it in the collection or the exhibit to show that part of farm life. You know how I said the One Chick Show sold out? Well, not completely. The Plucking Tree never sold. No surprise there, but I had to show what happens in summer when my broilers get big and fat—this is where I pluck them, and that is the view.

The Fiddleback: Who are some of your favorite artists? Are there literary influences or inspirations at work?

SVM: Earlier in life it was illustrators like N.C. Wyeth, L. Leslie Brooke, John Tenniel, Arthur Rackham. More recently, it’s printmaking and others: José Guadalupe Posada, Albrecht Durer, Hans Holbein the Younger, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Alphonse Mucha, Joseph Cornell, Laurence Hyde, Ray Gloeckler, Martin Mazorra, Deborah Mae Broad, Swoon, Walton Ford, Hatch Show Print, Kathryn Polk, and many others.

The Fiddleback: The themes and imagery in much of your work have been dealt with in art in a lot of ways. Your approach to portraying these animals is very intimate and unique. What do you think you do as an artist that may set you apart from others working with similar subject matter? Do you tend to draw a certain demographic?

SVM: There is always something specific I am trying to say when I plan out a piece. If I’m trying to show nobility, I’m going to draw the thing head on or looking up at it. I instinctively do not plan on doing a traditional portrait of an animal. I do not think “how can I make this cute?” It’s why I don’t do commissions. The best shot of an animal in its element might be its back end—the cocky way the terrier trots down the aisle between the lines of cows, in total control of the entire herd without even glancing up at any of them. In the portrait Quality Control, the owner of that dog wanted nothing to do with the painting. I didn’t paint it for him. I painted it for the city people who were going to come to a show about the Lives of Farm Dogs, so that they could see what this little dog’s working life was like. The demographic is hard to pinpoint, but the art sells in Paoli, Mount Horeb, and in Madison, purchased by local homeowners as well as more affluent folks from Chicago.

The Fiddleback: I first met you in a Mezzotint Workshop at Penland School of Crafts. Printmaking seems to have taken a big role in recent work, especially your large scale Relief and installation work. What does printmaking do aesthetically, formally or otherwise, that differs from your work in other media?

SVM: One of the reasons I went back to grad school was to learn relief printmaking. In 2007, you could see the change coming. Due to the economy, people couldn’t afford paintings like they used to and smaller things were selling better. I wanted to make my art affordable to many people and figured printmaking would be a good way to do that, especially since I’d always wanted to learn woodcut printing. I Got into grad school in fall of 2008 and started selling relief prints soon after.

Before that I had only learned etching in 2003, which was good for small intimate portraits of the characters featured in the painted works, but I wanted to learn how to do woodcuts and get away from the mark of the pen, stylus, brush, tiny detail and control of every mark. I wanted the cutting of the wood to be the line now—to give up the control and let the medium do the work. It was the chatter, I later learned, the incidental marks from the nature of the medium that was so appealing to me. Anyway, I applied to grad so that I could learn relief printing and get really good at. And then try to continue this portrayal of farm life—of raising animals for meat—in the form of big woodblocks.

Relief printmaking was everything that I thought it would be, and more. It’s physical, gestural and graphic—sort of the opposite of painting, and that’s a release. The medium takes over. I can’t completely control how it’s going to look, and I love that. I can’t work really slow in it and have to let the gouges take over and do their job. In working quickly, the chatter can happen and make the piece work. As in any medium, the trouble is learning when to stop cutting, but it’s a little clearer with relief than painting.

The Fiddleback: You seem to have a rock solid work ethic. I have seen this in a lot of Midwestern artists, especially those who have experience with the Farm lifestyle. Do you see a relationship between the demands of the Farm and the inner drive to be prolific?

SVM: I wish I could say it was the farm, but I grew up in the city with no work ethic and no issues. I had a great family life and was always encouraged in my two loves: art and sports.

I did well in school. I had it easy and didn’t have to work. It wasn’t until I was around hard-working folks and day laborers did I realize what I loved about work. There were the farmers in Latin America, and I worked as labor foreman in Central America in jungle, since I could wield a machete and talk Spanish and work side-by-side with these men. Then there were the blue-collar bricklayers I apprenticed with and worked with when I got back to the States supporting myself and my 1-year-old son. These experiences helped me realize that I really loved working hard, physically, for a living. When I returned to art, I treated it like a job. I need to make money to justify spending this many hours on the computer or in the studio, etc. Also, I think to justify it to my husband who is blue collar. I needed to show him that making art was work, and with long hours I could be successful and make money at it. I wanted to prove to him that it could be a real job.

But perhaps the biggest reason for the work ethic is deadlines. There’s the sheer terror of not getting everything done before a show. I plan each solo show one year in advance and then have to get everything done within that year. Once I commit, there’s no backing out. I’m afraid if I didn’t schedule the solo shows and make those deadlines, I probably wouldn’t get much work done.

And then, like I said before, it all started in 2002 with the realization that life is going to end at some point and I had better get my ass in gear because time is running out. Now I’ve got so many things I want to do I probably won’t get them all done, but at least I’m never bored. There’s always something that’s waiting to get started as soon as one is finished.

Another secret to getting lots of work done is working on 2-5 pieces at the same time. Then, if you get stuck with one, you can just work on another. You have no excuse for not working. You can’t walk away from the studio—there’s always something that can be worked on.

The Fiddleback: What’s next for you? Anything you want to try that you haven’t gotten to?

SVM: I would like to go back to painting again now that grad school is over and the Tunnel of Mortality is finished. I would like to regularly produce prints and paintings for Artisan Gallery in Paoli, which represents me, and I’d like to show in a few other galleries that are not in this area.

I need to find a chase for my old Potter Proofing Press so I can do letterpress and woodcut broadsides in my studio. I have no idea where to look for one or what site might have a list of printmaking classifieds that is recent or active. I’ve got lead type and most of everything else needed, and with wood cuts or wood engravings, I would like to make some awesome broadsides. Also, I was inspired by an amazing print show this summer in Milwaukee that showed posters of Paris from the 1890s. I plan on trying some tall figurative work inspired by the posters of Mucha, but instead of lithographs I would do woodcuts.

——–

svmedaris.com.