Music Reviews, 08/2012

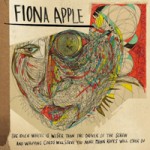

Fiona Apple | The Idler Wheel is Wiser…

Label: Epic

by Andrew Terhune

While accepting Best New Artist at the 1997 VMAs, Fiona Apple declared: “This world is bullshit!” While this statement may have been a bit ill-conceived, the spontaneity and anger was refreshing.

While accepting Best New Artist at the 1997 VMAs, Fiona Apple declared: “This world is bullshit!” While this statement may have been a bit ill-conceived, the spontaneity and anger was refreshing.

In the years since Tidal and even When the Pawn…, Apple seems to have focused this anger and produced some of the last decade’s most compelling music, most notably 2005’s Extraordinary Machine. Fifteen years after VMA host Chris Rock dubbed her ‘Fiona X’, the resilient songstress is back. Apple has been battle-tested and her fourth album – her first in seven years – shows her scars. In short, the invigorating The Idler Wheel is Wiser than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords Will Serve You More than Ropes Will Ever Do is a triumph and well worth the wait.

With odd percussion and raw clanging piano, the songs have a well-worn, lived-in quality that feels familiar, but ultimately altogether new. The arrangements are ballsy and Apple’s vocals dance across a musical landscape that will continually surprise well beyond the first listen.

Volatile as always, Apple presents songs like “Daredevil” and “Left Alone” with a gleefully aggressive snarl. While there are somber moments throughout (“Valentine” and “Jonathan”), the entire album swells with a looming frenetic energy. The swinging choruses of lead-single “Every Single Night” and the sing-songy “Periphery” show that she can still crack a smile. The beautiful closer “Hot Knife” borders on joyful.

Track-for-track, The Idler Wheel… is a storm cloud of a record—sometimes it rains, sometimes it pours. It’s a welcome addition to the Fiona Apple canon. Let’s hope we don’t have to wait so long for the next installment.

Dirty Projectors | Swing Lo Magellan

Label: Domino

by Joshua Cross

Swing Lo Magellan, the latest output from Brooklyn’s Dirty Projectors, gives me existential anxiety as a music reviewer. A lot has been said about this record already, so I don’t know what I could say about it that hasn’t been said, or whether any of what I could say would be true.

Swing Lo Magellan, the latest output from Brooklyn’s Dirty Projectors, gives me existential anxiety as a music reviewer. A lot has been said about this record already, so I don’t know what I could say about it that hasn’t been said, or whether any of what I could say would be true.

Like other reviewers, I could say Swing Lo Magellan is Dirty Projectors’ most accessible album yet, and yeah, that’s true. But that’s like saying As I Lay Dying is Faulkner’s most accessible book. Again, true, but saying it’s more accessible doesn’t mean it’s accessible. Dirty Projectors aren’t about to get Top 40 play. Your mom isn’t about to buy their CD from Wal-Mart. The songs are still complicated and challenging. They defy conventional notions, buttressed by high school dramadies and glee club renditions, of what pop music should sound like. And while overall Magellan may not be as challenging as Bitte Orca was, it lacks a standout single to rival “Stillness Is the Move,” though the title track and “Dance for You” try their darnedest.

I could praise the album’s vocals, and they are well deserving of praise. Dave Longstreth’s voice is at its best on this record, at its clearest and most emotive. Amber Coffman and Haley Dekle continue to compliment Longstreth admirably, providing soft contrast to his sharp edge. But, while true, this still doesn’t get at the whole truth. The vocals are the beautiful core of the record, but that’s true about every Dirty Projectors release. The contrast between male and female voices creates a wonderful dynamic, but that’s been true ever since Coffman joined the band in 2006. But even beyond that, praising the vocals isn’t quite the whole truth. Longstreth, Coffman, and Dekle are at their best here, but they’ve lost Angel Deradoorian’s charm, and they’ve lost some of the odd, borderline off-key harmonies that made Dirty Projectors sound like an entity unto themselves.

I could praise the music for being more direct, less ornate, less idiosyncratic. But I would feel like I was just using reviewer-speak to avoid saying “it’s less weird, so you might like it more.” And again, this wouldn’t be true, or at least wholly true. We’re still talking matters of degree. Longstreth’s songcraft may be more direct on this record. It may be less ornate. But it’s still challenging, and that challenge is what makes Dirty Projectors work. It’s not for everyone, but it works.

I could praise Longstreth for being more personal (and thus implying less pretentious) in his songwriting. But other people have already said that about this album. And besides, I think that’s missing the point.

I could compare Magellan to other artists and other albums. But really, I can’t think of any bands that sound quite like this other than the Dirty Projectors. And then we’d be in a self-referential feedback loop.

So I don’t know anything original or true to tell you about this record. I could tell you that a girl I used to know would absolutely love this album, if for no reason beyond the fact that handclaps form a percussive foundation on every song and she liked any song that had handclaps. That would be true, and it would be original. But it would be original coming from her, not from me since it’s her quirk and not mine. Besides, she isn’t writing this, so she can hardly tell you it’s a good album.

And it is. It’s a very good album, one of the best of 2012 so far. At the fundamental level, that’s what I want to tell you in this review. I think this is a good album, and I think you should give it a listen and decide for yourself whether you agree. I can think of nothing more true to say about Swing Lo Magellan, or any original way of saying it.

Twin Shadow | Confess

Label: 4AD

by James Brubaker

Let’s be honest—we all groan a little bit whenever we hear young, romantically minded people think about their lives in terms of cinema. Before this trope was so irritating (perhaps when we were those young, romantically minded people) Paul Thomas Anderson made great use of said trope in Magnolia when Phil Parma is on the phone trying to contact Frank Mackey and he compares his circumstances to scenes in movies where dying men are trying to track down their long lost sons, and he ends his argument by saying, “This is the scene of the movie where you help me out.”

Let’s be honest—we all groan a little bit whenever we hear young, romantically minded people think about their lives in terms of cinema. Before this trope was so irritating (perhaps when we were those young, romantically minded people) Paul Thomas Anderson made great use of said trope in Magnolia when Phil Parma is on the phone trying to contact Frank Mackey and he compares his circumstances to scenes in movies where dying men are trying to track down their long lost sons, and he ends his argument by saying, “This is the scene of the movie where you help me out.”

The reason I mention Magnolia now is because Confess—Twin Shadow’s follow up to Forget, a very good debut album—is an album about the need some folks feel to live inside of large, romantic worlds, despite those worlds’ inherent artifice. Sure, the notion is born from the raw immediacy of youth and, at least for Twin Shadow’s George Lewis jr. (not to mention Anderson during his Magnolia years), a steady supply of cocaine, but that doesn’t stop the sentiment from ringing true to the rest of us, be it as an enticement to live a little larger, or as a critique of the inherent desperation on which such a worldview is founded.

Lewis’ palette for his grand romantic visions is, as on his debut, rooted in the romanticism of 80’s pop. What sets Confess apart from its predecessor, though, is Twin Shadow’s willingness to make the songs bigger and more dramatic. The album still draws on acts like The Cure, The Smiths, and Modern English, but the 80’s Springsteen vibes that show up in Lewis’ vocal delivery on “Run My Heart,” and “I Don’t Care,” is genuinely surprising. Likewise, the grand gestures of the album’s vocals are album echoed by the arrangements, which include drumlines, soaring melodic hooks, and dramatic synth flourishes. But all of the heightened drama and exacting attention to detail aren’t the story here—strip these out of each song and there is still something impressive happening in every song.

For all the drama, steel drums, and martial snare-line taps that gives a song like album opener “Golden Light” its shape, that song so thoroughly incorporates the 80’s romantic aesthetic that we could slip it in over the closing credits of Karate Kid pt. 2, and many viewers wouldn’t notice. At the same time, the song subtly warps elements of its production (check out the weirdly phased countermelody during the chorus) to firmly ground itself in 2012. What becomes clear as the album progresses is that Lewis has made an album completely of 2012, that just happens to pin its romantic longing for a bigger, more dramatic life on the impossible nostalgia of the 80’s.

But what is the sum of all this romance, all of this bigness? Why is Twin Shadow spending so much time basking in the hipster runoff of 80’s nostalgia? Because, however pretentious or embarrassing it may seem, this is the part of the movie when the rough-around-the-edges, tortured, young artist is allowed to become beautiful, is imbued with an existence-validating sense of love and/or pain. This irrational, desperate desire to create and inhabit this romantic, artificial past-world is hinted at in Lewis’ lyrics. On, “The One,” Lewis sings, “I’m in love with my memories”; on “When the Movie’s Over,” he sings, “I’ll cry when the movie’s over”; and on “I Don’t Care,” he sings, “I don’t care/Long as I can dance you round the room while you lie to me,” with the dancer and the liar changing places in the final verse.

Lewis’ songs aren’t simply nostalgic for the past, they are about a desperate need to cling to that past, to cling to an artificial romance that doesn’t belong here, in the present, but which we construct from myths of past decades’ memories and culture. To that end, the thing that Lewis is confessing, here, is that he, or his character, desperately needs those romantic myths to make sense of an otherwise underwhelming existence, and he’s willing to cheat, lie, and steal to hang on to them. As such, on Confess the gestures are grand, the emotions heightened, and the scope, immense—because that’s what Lewis, and by extension many of his listeners, expect, what they were promised by nostalgia, and by popular culture. You and me, we may have learned that life is lived in the details, that small gesture can be the most meaningful, that life can be boring, and hard, and that’s okay—but for George Lewis Jr. and his fans, for better or for worse, this is the part of the movie where they feel alive, and whether we agree or disagree with their stance on the romantic past, the extraordinary sadness and desire that underlies their desperation is utterly compelling.

The Antlers | Undersea

Label: ANTI-

by Joshua Cross

Undersea is an anomaly in time. The Antlers have found some wormhole or built a flux capacitor. For their ANTI- debut they were able to travel back to 2010 in order to write and record the missing link in their discography, a perfect bridge between 2009’s Hospice and 2011’s Burst Apart, all in the guise of a four song EP.

Undersea is an anomaly in time. The Antlers have found some wormhole or built a flux capacitor. For their ANTI- debut they were able to travel back to 2010 in order to write and record the missing link in their discography, a perfect bridge between 2009’s Hospice and 2011’s Burst Apart, all in the guise of a four song EP.

Burst Apart was a good record, perhaps one of last year’s more underrated albums, one that didn’t quite make the cut in our Top 30 of 2011 but did receive votes. Burst Apart’s biggest flaw was not that it wasn’t Hospice, it was that it was nothing like Hospice. The Antlers’ sound changed too much too fast, from one of the most heart-wrenching albums to ever be called lo-fi, to one of expansively produced, electronic grandeur. Styles evolve or they die, but evolution is a slow burn over centuries, not a switch flipped from one album to the next.

So we should be glad The Antlers have somehow learned to manipulate space-time, and hope they continue to use their powers for good. And Undersea is good. Its four tracks combine the pace and tone (minus all the abuse and dying) of Hospice with the production and atmosphere of Burst Apart.

Undersea could not be more appropriately titled. Each song sounds like it was recorded in a submarine by highly sophisticated machinery impervious to the pressures of the deep. Water permeates the sounds we hear and the images the hearer conjures. We emerge from these four songs—each one able to stand by itself, but, like the oceans, forming one larger body when seen from a distance—feeling damp, Peter Silberman’s gorgeously strained voice dripping from our wetsuits.

Or perhaps I have it all wrong. Perhaps The Antlers are no time travelers. Perhaps Undersea is no bridge between the last two Antlers LPs, but instead a bridge across future waters, a bridge linking where they’ve been with where they will go. I like this scenario better. If it’s true, then we have plenty to anticipate from these guys. Plus, if they’re not traveling through space-time then I don’t have to worry about The Antlers creating a paradox or being eradicated by Blorgons. And really, I have enough anxiety without worrying about paradoxes and Blorgons.

DIIV | Oshin

Label: Captured Tracks

by Brian Flota

DIIV (pronounced “Dive”) is the kind of band I’m rooting for. Why? There are several reasons. They are the kind of band that can be divisive because the most current musical trends are not really part of their repertoire. They are dream pop nostalgists: The Cure’s Disintegration and early Interpol are clear points of reference, as their songs slowly build toward their major themes while constantly harnessing a Hemi-powered drive (my apologies to Bruce Springsteen). Yet they don’t really sound like either act. They are also a really good, tight band that lacks a musical gimmick (unless one thinks their “bad spelling” derives from the crude 70s UK glam rockers Slade). Because of the record’s propensity for catchy minor chord-heavy compositions and lead vocalist Zachary Cole Smith’s fairly inflexible emotional and vocal pitch, it can be same-songy. Similarly, ex-Smith Westerns drummer Colby Hewitt contributes time-perfect beats with gusto, yet avoids flashy fills. Yet, DIIV’s first album, Oshin, combines the accelerating elements of 00s dance punk with post-rock instrumental passages and early 90s shoe gaze into one largely successful unit.

DIIV (pronounced “Dive”) is the kind of band I’m rooting for. Why? There are several reasons. They are the kind of band that can be divisive because the most current musical trends are not really part of their repertoire. They are dream pop nostalgists: The Cure’s Disintegration and early Interpol are clear points of reference, as their songs slowly build toward their major themes while constantly harnessing a Hemi-powered drive (my apologies to Bruce Springsteen). Yet they don’t really sound like either act. They are also a really good, tight band that lacks a musical gimmick (unless one thinks their “bad spelling” derives from the crude 70s UK glam rockers Slade). Because of the record’s propensity for catchy minor chord-heavy compositions and lead vocalist Zachary Cole Smith’s fairly inflexible emotional and vocal pitch, it can be same-songy. Similarly, ex-Smith Westerns drummer Colby Hewitt contributes time-perfect beats with gusto, yet avoids flashy fills. Yet, DIIV’s first album, Oshin, combines the accelerating elements of 00s dance punk with post-rock instrumental passages and early 90s shoe gaze into one largely successful unit.

The record begins with the instrumental “(Druun),” which musically sets the tone for the album. Hewitt’s driving beat is matched by fluid, carefully manicured guitar leads that are gushy and atmospheric. The chorus and reverb effects found in the guitars are carried over to Smith’s vocals on the second track, “Past Lives,” as they further perfect their post-rock, post-shoegaze brand of contemporary rock. As the record works toward its center, the tracks gradually gain momentum and even a modicum of musical ferocity. The album’s best moment are in the middle. The almost-instrumental “Air Conditioning” shows off a hypnotic bass line and practically pushes Smith’s ethereally-treated vocals into the background so that they become another instrument. “How Long Have You Known” is probably the catchiest number on this set, while “Wait” is the closest the album retreats to 80s new wave nostalgia, and this is not a bad thing. The rest of the album can’t quite keep up this momentum, though “Oshin (Subsume),” which harkens back to Slowdive and the long-forgotten shoegaze act Blind Mr. Jones, and “Doused” come close. While Oshin may lack a certain inventiveness, like the herky-jerky Talking Heads rhythms of the Dirty Projectors or the sunshine neo-soul of Frank Ocean, it is one of those rare albums that genuinely lacks a weak track.

Bike Thiefs | Loot Bag

Label: Independent

by Jack Caseros

No one likes bike thieves. So it seems appropriate that Loot Bag, the debut release from Mississauga (Ontario, Canada) indie band, Bike Thiefs, is rife with self-loathing and desperation.

No one likes bike thieves. So it seems appropriate that Loot Bag, the debut release from Mississauga (Ontario, Canada) indie band, Bike Thiefs, is rife with self-loathing and desperation.

But unlike Thoreau, Bike Thiefs’ desperation is anything but quiet. Several tracks feature a Pixies-esque sing-song scream intertwined with a soul-wrenching melody—the bi-polar equivalent of a rebel yell, backed by layered guitars riffs, a grungy bass line, and tick-tock tight drums.

The drums hold the whole album together—and to really understand this, you need to know a little background about the boys in Bike Thiefs. Guitarist/vocalist/keyboardist Marko Woloshyn and bassist/vocalist Kyle Davidson were founding members of We, The Firemakers, whose five-piece explored a heavy, technically-complex brand of rock. But like many underground indie bands, We, The Firemakers fell apart. Whether it was due to stress, frustration, or just plain laziness, the end result was a fractured membership that went on to join other Mississauga bands.

Marko and Kyle were the lynchpins in We, The Firemakers success. And like much artistic brilliance, a touch of manic-depression made their work all the more raw and touching. That same madness made them essentially dysfunctional. At that point, the lynchpins needed a lynchpin. As the band states on their Facebook page, drummer Ryan Perry was, “[…] injected into Bike Thiefs like a beta blocker.”

So, unlike We, The Firemakers, Bike Thiefs dismiss hubris in an attempt to puncture right into the lung: “Stick to the mattress and the sentiment,” Marko sings in “Don’t Worry”, exemplifying the sardonic realism that paints the album.

But like any good loot bag, the album is a collection: from a dancey groove for large women (“Big Fat Beautiful”) to a morose crooner (“A Tangent”); from a hipster Mexican stand-off (“Ultimo Hombre”) to throaty punk-folk (“Wadega”). “Soft Exit” and “Escape Artist” seem to be where Bike Thiefs are most comfortable—Marko and Kyle compliment each other’s vocal styles perfectly, and their terse cynicism finds its clearest voice (“If I see you again, I hope you’re crying in a clinic somewhere,” Kyle belts out in “Escape Artist”). “Pocket Bike” is a sincere conclusion. At over eight minutes, and complete with a touching (but kind of creepy) voicemail message, it features the penultimate sing along (“Last call, sing along, bow your head and walk away”).

More than novelty erasers and plastic slinkies, this Loot Bag is one of those rare loot bags from a rich friend that has action figures, little books, and a mini BMX bike. And if you never had a rich friend as a kid, consider this your opportunity to make friends with a band that won’t leave you disappointed with their party favours.

Jack Caseros is a Canadian writer whose fiction has appeared online and is forthcoming in print. His first novel, Onwards & Outwards, was released to zero acclaim. You can read more about Jack at: www.jackcaseros.webs.com.

Purity Ring | Shrines

Label: 4AD

by James Brubaker

Call it cognitive dissonance, call it creative juxtaposition, call it artful anachronism—whatever you want to call it, it is Purity Ring’s smashing together of two disparate elements that makes them so compelling. On the surface, this Canadian duo’s debut album Shrines is pleasant enough musically, merging elements of contemporary hip hop and R&B with hints of dubstep and electronic experimentation. Slick beats, heavy bass lines, and vocals that are presented at times as crisp and clear—the stuff of sixties girl group pop—and others as pitch shifted and unsettling come together seamlessly to create an album that sounds very of its moment.

Call it cognitive dissonance, call it creative juxtaposition, call it artful anachronism—whatever you want to call it, it is Purity Ring’s smashing together of two disparate elements that makes them so compelling. On the surface, this Canadian duo’s debut album Shrines is pleasant enough musically, merging elements of contemporary hip hop and R&B with hints of dubstep and electronic experimentation. Slick beats, heavy bass lines, and vocals that are presented at times as crisp and clear—the stuff of sixties girl group pop—and others as pitch shifted and unsettling come together seamlessly to create an album that sounds very of its moment.

Where Purity Ring finds some real thematic depth that pushes Shrines beyond its contemporary context, however, is in Megan James’ out of time, out of place, and out-of-her-goddam-mind lyrics. Against Corrin Roddick-crafted sonic backdrops that vaguely sound as if they could be playing in the background in a club scene from a sci-fi movie, James sings about nature, the body and mortality with a fervor for language and metaphor born from the depths of antiquity, and with a peculiar mythos too match. While the lyrics, at times, scan as if pulled from the pages of an undergrad’s private diary (word on the street, and by street I mean Wikipedia, is that this might be the case), their peculiar, dark world view and emphasis on the natural provide a compelling counterpoint to Roddick’s dreamy dance-scapes.

On “Crawlersout,” James opens the album by proclaiming, “Sea water is flowing/from the middle of my thighs,” over a sparkling, elegantly stuttering beat and glowing synth melody, establishing an unsettling connection between the natural world and the body that is explored on almost every song on the album. On “Saltkin,” after proclaiming “There is a cult inside of me,” James suggests, over a quiet passage of pulsing keyboards, that “Into a blood-bound, cease rounded fury our bodies will return.” It is this obsession with the liminal space between body and nature, between inside and outside, between the abject and the sublime that compels James’ lyrics and pushes up against Roddick’s mechanical, austere compositions, giving the songs a sense of being untethered from time; James’ lyrics pull backwards while Roddick’s compositions dance in the present with an eye toward the future.

Such tensions between the mechanical and the human has become something of a reoccurring theme in a handful of exceptional releases this year. On albums like Laurel Halo’s Quarantine, and Motion Sickness of Time Travel’s self-titled album, these conflicts are more explicitly illustrated as the mechanical and organic impinge on one another’s spaces, creating tension and conflict. On Shrine, Purity Ring don’t go out of their way to force such conflicts on their songs, choosing instead to let the surreal juxtaposition of James’ anachronisms to weirdly coexist in otherwise contemporary sounding songs. Shrine might have been a stronger album had these tensions been explored a bit more explicitly, but the end result is still a wild and surprising exploration of how two disparate ideas can come together to make songs that are both compelling and unsettling.

The Smashing Pumpkins | Oceania

Label: Caroline/EMI/Martha’s Music

by David Branstetter

Whether or not you like Oceania, the new Smashing Pumpkins album, depends squarely upon how much you bought into the hype surrounding the band at the height of their popularity. If you can get past the fact that Corgan is the only original member of the band and can listen to the album with an open mind you might find yourself happy that you did.

Whether or not you like Oceania, the new Smashing Pumpkins album, depends squarely upon how much you bought into the hype surrounding the band at the height of their popularity. If you can get past the fact that Corgan is the only original member of the band and can listen to the album with an open mind you might find yourself happy that you did.

Smashing Pumpkins as a band has always been about defying expectations, looking left but often turning right. Where the band could have been trying to duplicate their hits with “sound-a-like” singles and endless greatest hit tours, the Pumpkins have taken the high road and have always put artistic integrity first. Corgan could have treated his new band as “hired guns” but instead he is forging ahead with them and creating a new legacy.

Oceania never raises to the heights of the Pumpkins’ best work but it never sinks to the lows of material from ’98 on. In a bold move, the album doesn’t contain any obvious singles and was conceived to be listened to as a singular unit. Yet songs like the “Celestials” bubble out of the frame work looking for a home on the radio. One of best things about this album is the contributions from the other band members. There are moments on the record where you can feel the band solidify and take big steps together as a unit. It’s important to note that this version of Smashing Pumpkins feels the most like a band effort since 1995’s Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness.

You can hear the DNA of some of the Pumpkins best work scattered through the tracks. The rocking opener, “Quasar,” is reminiscent of Siamese Dream’s “Cherub Rock” but then quickly turns into something more akin to the jam-centric “Superchrist.” “My Love is Winter” tries to venture into single territory but it doesn’t retain the sincerity of “The Celestials” or “Violet Rays.”

Title track “Oceania” showcases the new band’s strengths. Written in three parts, the track takes the listener on a powerful journey. By the time the song arrives at its acoustic bridge listeners are likely to feel genuinely lulled into a place of serenity. Corgan gently pleads “Try to wait on me” and we’re inclined to do so. Just as we begin to feel at peace in Corgan’s world, Nicole Fiorentino’s seductive bass line pulls the song out of serenity and back into a dizzying feeling of hopelessness. It’s a classic Pumpkins moment. The epic track is then capped off with a solo that seems to come down from above to set the world on fire.

The absolute best track is the meditative “Pale Horse.” The timpani and the mechanical ratchet tap of Mike Byrne’s drum kit work together with a bold bass line by Fiorentino. Soothing background vocals and the gentle chorus of “Thora Zine” peacefully lead us along. Unlike Corgan’s work from the last decade, this song is no hurry to get the next track.

As if to say “let’s get back to work,” “The Chimera” jumps back in with a fun up-tempo piece that doesn’t feel forced and at times reminds me of Siamese Dream’s “Rocket.” “Inkless,” another standout track, retains some of the upbeat energy of later-era Zeitgeist tracks but really makes it work within a new context.

“Wildflower” is the typical Pumpkin’s closing number. Unlike the rest of the album, Corgan’s voice doesn’t seem right for the track. It may have worked better without vocals but the beautiful refrain “Wasted along the way” justifies the song’s existence. The gorgeous track is laced with interesting background effects and synths making it a strong finish to Oceania.

I haven’t said anything about new guitarist Jeff Schroeder but honestly I can’t tell the difference between Corgan and Schroeder’s playing. It’s a compliment that he is able to blend in so well with Corgan’s style. I do know that some of the monster solos on this record are duel parts played and recorded at the same time by both members.

Compared to recent output from the Pumpkins’ contemporaries, Oceania is, as a whole, more memorable than Pearl Jam’s Backspacer and Stone Temple Pilots’ self-titled effort. Oceania may not be an essential Pumpkins album but it could be the linchpin that sees Corgan turn around his much maligned career.