Book Reviews, 02/2013

This issue

Kurt Vonnegut, Letters

George Saunders, Tenth of December

Nate Slawson, Panic Attack, U.S.A.

Sarah Rose Etter, Tongue Party

Juliann Garey, Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See

Kurt Vonnegut | Letters

Delacorte, 2012

by Brian Gebhart

Kurt Vonnegut was a man of many contradictions: a humorist and a melancholic, a World War II veteran who became a pacifist, and a proud Midwesterner who chose to spend most of his adult life in Cape Cod and New York City. In his letters, Vonnegut employs the same contradictory impulses that suffuse his novels and short stories and essays. He is warm but gruff. He is charming yet brutally honest. He is cheerful yet fatalistic, often to the point of despair. Most strikingly, he has a great capacity for both raw emotion and unapologetic silliness.

Kurt Vonnegut was a man of many contradictions: a humorist and a melancholic, a World War II veteran who became a pacifist, and a proud Midwesterner who chose to spend most of his adult life in Cape Cod and New York City. In his letters, Vonnegut employs the same contradictory impulses that suffuse his novels and short stories and essays. He is warm but gruff. He is charming yet brutally honest. He is cheerful yet fatalistic, often to the point of despair. Most strikingly, he has a great capacity for both raw emotion and unapologetic silliness.

So the tremendous wit and singular style evident in Kurt Vonnegut: Letters (edited by Dan Wakefield) will be familiar to anyone who has read the author’s work. But the correspondence also serves as a sort of accidental autobiography. While the story is incomplete—since we only get Vonnegut’s point of view, and only on the subjects he chooses to write about—the letters are also revealing in a way that a self-contained narrative wouldn’t be. This is particularly true regarding Vonnegut’s family life, which was complex and often heartbreaking.

Like many funny people, Vonnegut’s comic impulses seemed to arise from the dark waters of a traumatic past. He admits in one letter that his depression may have stemmed from his mother’s suicide when he was a young man—just the first in a litany of tragic events to befall him. There is, of course, the famous episode recounted in Slaughterhouse-Five, in which he Vonnegut witnesses the firebombing of Dresden, a memory that haunted him throughout his life. In 1958, Vonnegut’s sister, Alice, died of cancer, and just hours later her husband was killed in a train crash. So Vonnegut and his wife, Jane, adopted Alice’s three children, forming a bustling household with six kids. This placed a strain on Kurt and Jane’s marriage. During the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, Vonnegut was still struggling to make a consistent living as a writer. He opened a Saab dealership, then closed it less than a year later. He contracted to produce a sculpture for a motel at Logan International Airport. He even proposed to his agent a short-story collection titled, Clean Stories for Clean People in Drugstores and Bus Depots, and insisted in a second letter that he wasn’t joking. Vonnegut finally landed a steady paycheck in 1965, when he accepted a job at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, but he later admitted to his daughter Nanette that he had left in large part because of marital strife.

The letters between Vonnegut and his immediate family are the most revealing and affecting in the collection, particularly those to Nanette, who was the youngest child from his first marriage. The tone of his letters indicates that she was loath to forgive him for leaving Jane. Vonnegut alternately showers her with expressions of love and chides her for her reticence: “Well—it could go two ways with us: you could figure you had been ditched by your father, and you could mourn about that. Or we could keep in touch and come to love each other even more than we have before…We’ve got to wish each other happy birthdays, and ask how work is going, and tell each other jokes, and all that.” This correspondence reveals one more contradiction: it seems as though Vonnegut’s relationships were strongest when nourished from afar, a dilemma he was acutely aware of. Shortly after moving to New York, he wrote to a friend: “My children think I’m foolish to lead the life I do, and I think they’re correct. But I can’t think of another life that would comfort and calm me.”

For true Vonnegut fans, the appeal of this detailed portrait of the author’s life is obvious. But one needn’t be a devotee in order to appreciate Letters. Anyone interested in writing or publishing will find many hilarious anecdotes and keen observations. Since Vonnegut’s career spanned the entire second half of the twentieth century, it charts the history of post-war American literature almost perfectly. He began publishing short stories in weekly magazines like Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post, in the days when selling four or five stories a year could keep a roof over one’s head. His career weathered the death of those magazines and the consolidation of the publishing industry—both of which he lamented—as well as his sudden elevation to the status of countercultural icon—an honor of which he was always dubious. Of course, while some things change, others remain the same. In a letter from 1954, Vonnegut complains about one feature of the literary world that’s still with us today: “Unsettling business for an artist, where everything that happens in New York has universality, and everything that happens outside is ethnography.” So says a guy who would follow his fame straight to Manhattan.

Above all, anyone who cares about good writing will feel a twinge of nostalgia for an era when people wrote letters. Vonnegut’s correspondents include many of the great literary figures of his day: Norman Mailer, Nelson Algren, Bernard Malamud, Anne Sexton, William Meredith, Gail Godwin, and Isaac Bashevis Singer, as well as the odd missive to Jack Nicholson, Stephen Jay Gould, and the editors of The New York Times. But ultimately, the substance of Letters matters far more than the letters’ recipients, and Vonnegut does not disappoint. For whether he was writing to a friend or family member, penning lines of praise for a colleague’s work or a unleashing a jovial tirade at the Junior League of Indianapolis, Vonnegut always followed the instructions he once gave his students at Iowa. “As for your term papers,” he wrote, “I should like them to be both cynical and religious. I want you to adore the Universe, to be easily delighted, but to be prompt as well with impatience… Be yourself. Be unique… Do not bubble. Do not spin your wheels. Use words I know.”

George Saunders | Tenth of December

Random House

by Sally Franson

Perhaps it’s because the big 3-0 is looming on the horizon for this reviewer, or perhaps because subzero temperatures have triggered some kind of seasonal affective morbidity, but for whatever reason, it appears that death is having sort of a moment in our ageist, weight-obsessed, gluten-free culture. Case in point: this recent essay on The New York Times

Perhaps it’s because the big 3-0 is looming on the horizon for this reviewer, or perhaps because subzero temperatures have triggered some kind of seasonal affective morbidity, but for whatever reason, it appears that death is having sort of a moment in our ageist, weight-obsessed, gluten-free culture. Case in point: this recent essay on The New York Times

But our wants and needs are very often at cross-purposes, especially when it comes to contemplating our terminal state – which, coincidentally, is the only real birthright we have. Death, for most of us, is the ultimate monster in the closet: the longer it stays hidden behind the door, the more terrifying it becomes. Subsequently we have always relied upon artists (Dante, Milton, the list goes on ad infinitum) to nudge us – some gently, some brutally – toward this proverbial closet, to impel us toward the shadows, to help us be brave. And no one is better at this nudging right now than George Saunders, whose new collection of stories, Tenth of December, has garnered such universal acclaim, and by such a wide range of publications, that it feels almost silly to discuss it any further.

Yet while it’s old hat now to pontificate about Saunders’ verbal dexterity and syntactical brilliance and big heart and clever, Vonnegutian dystopias, what remains the most abiding and compelling, and in some ways least-articulated, aspect of his work is its willingness, for lack of a more literary term, “go there.” Here is a writer not only unafraid of sentiment, but also unafraid of asking Big Questions without guile or predetermined agenda or cheap/hip irony. Jeff, the narrator of “Escape from Spiderhead,” a story about convicted criminals undergoing experiments for emotion- and personality-enhancing drugs, illuminates this sincerity clearly within the text. “Why are such beautiful beloved vessels,” he wonders, bewildered, as he watches a former lover suffer under an extreme depressant, “made slaves to so much pain?”

This question can only be answered by another question: when was the last time you read an author whose ambitions were so tender and vast? Unlike Amour, Michael Haneke’s Oscar-nominated film that has drawn attention for its unflinching portrayal of a slow mortal decline, Saunders’ stories sidle up to death from a side angle. In Amour, viewers are trapped alongside the characters in a small Parisian apartment, confined to just a few rooms for the entire duration of the film. Death – literally, at a certain point – begins seeping through the walls, and through the use of long shots and intense scenes of bodily humiliation, Haneke commands his viewers to bear witness. Conversely, Saunders possesses a lighter touch, allowing insight into the terminal human condition to bubble up organically, amidst the inanity and absurdity and confusion of daily life.

For example, in “The Semplica Girl Diaries,” a story that took Saunders fifteen years to write and is arguably the best in the collection, the middle-aged father who narrates via a fragmented journal has a hilariously averse and authentic reaction to a peer/coworker’s funeral. “Funeral so sad, lunch = heaven,” he writes, “Eat three roast beef sandwiches in row off paper plate.” Despite his efforts to distance himself from death, however, he finds himself haunted by what he witnessed: “Can it be true? That I will die? That Pam, kids will die? Is awful. Why were we put here, so inclined to live, when end of our story = death? That harsh. That cruel. Do not like.”

“The Semplica Girl Diaries” is about more than just death (namely materialism, class, globalization, parenthood, affluenza – the list goes blessedly on), as are the rest of the stories in Tenth of December (“Victory Lap” is a must-read. So’s “Puppy.”), but an undercurrent of loss acts as a thru-line through the collection. And not just any loss. The Big Loss. The loss manifested by a punch-in-the-gut realization that life will one day end. What heartbreak. “It wasn’t fair,” despairs Eber, one of the narrators in the eponymous story who, the reader learns, is slowly dying of a brain tumor, “It happened to everyone supposedly but now it was happening specifically to him. He’d kept waiting for some special dispensation.” We all are, which is the most tragic thing about us. But, as Saunders deftly reveals again and again, it’s the most darkly comic, too.

One has the sense that Saunders walked all the way into his own monster-filled closet in order to write these stories, for a sense of expansiveness accompanies the sometimes very serious subject matter. From the emptiness, the Buddhists say, comes freedom. (Saunders is a longtime practitioner.) “There could still be many – many drops of goodness,” Eber thinks, as he considers the future, “many drops of happy – of good fellowship.” When taken out of context this might sound trite or saccharine, but in fact it’s the opposite. Eber finds a deep gladness only after he fully considers the “strange or disgusting” things he might do while dying, the lessening that would inevitably accompany the end of his life. For a moment he can hold up joy/sorrow and life/death, simultaneously, and Saunders, like all great artists, is encouraging us to do the same. Knowing what Eber knew, “Did he still want it? Did he still want to live?” His answer emerges from the soft spot that’s inside all of us: yes, yes, oh, God, yes please.

Nate Slawson | Panic Attack, U.S.A.

YesYes Books, 2011

by Kevin O’Rourke

1993 was one hell of a year. Czechoslovakia split up. The World Trade Center was bombed. The Cowboys beat the Bills in the Super Bowl. Windows NT was released.

1993 was one hell of a year. Czechoslovakia split up. The World Trade Center was bombed. The Cowboys beat the Bills in the Super Bowl. Windows NT was released.

As was the indie rock band Jawbreaker’s record 24 Hour Revenge Therapy. Clocking in at slightly less than three minutes, the record’s highlight (for me, at any rate) is its eighth song, “Do You Still Hate Me?” Addressed to some unidentified second person, the song’s lyrics read like a letter to a lost lover. To be more specific, a letter in which the foolish nature of lovers’ quarrels is questioned, such as when Blake Schwarzenbach sings that “we’re getting older / but we’re acting younger / we should be smarter / it seems we’re getting dumber.”

The ninth poem of Nate Slawson’s Panic Attack, U.S.A. directly references Jawbreaker. In that poem — “You Are Lunch Hour Revenge Therapy,” from the “Teenage Sonnets” section of the book, which are all titled ‘You Are X’ — the speaker’s longing for whoever the you is is also tinged with a degree of self-loathing and desperation. Lines 6-11 read:

or can you tell me the truth once

& for all do you hate me? I ache

for you in spite of you & me &

human fucking error I love you

pill-crush & propeller sleep I

love you kill switch & dirty movies

A similar sense of desperate longing, expressed in breathless lines with few end stops and lots of enjambment, runs throughout much of PAUSA.[1] Indeed, some form of the word “you” is found in every single one of this collection’s 57 poems. If one wanted to be dismissive, one could say that if you’ve read one Nate Slawson poem, then you’ve read them all.

But that wouldn’t be fair, because this book is a wonderful example of how to establish and run with a style, one which is affecting & mesmerizing & often quite funny. Moreover, pointing out that so many of the poems are directly addressed to some you —really, aren’t lots of poems in general? — doesn’t do justice to the fact that the person, or persons, addressed seems to shift as the book progresses, not to mention Slawson’s use of this mode of address to convey information about his speaker(s). Nor does dismissing many of these poems as similar address his use of highly specific, yet accessible (no Pound-esque classics references here) real-world information to add layers of interest and detail. From “An Essay About the Universe”:

What sucks about the soul

is not knowing if it ends

like a parade ends or like

a night in a Cincinnati

hotel room I know when

stars die they explode

Mahler 6/8 hellfire

the sky grows epileptic

helium it’s very romantic

This is one of several mentions of Cincinnati in the book. The Midwest features prominently in PAUSA , as does music, particularly indie rock (see above re: Jawbreaker), though Slawson also shows us he’s not too cool for school with the odd Bo Diddley, or Mahler, reference.

And I though I’m not sure PAUSA’s speaker(s) necessarily grows & learns as the book progresses — there is no concrete narrative thread, as narration does not seem to be this book’s main interest — the poems do grow increasingly complex. The book’s first section, the aforementioned “Teenage Sonnets,” deal with unrequited love and frustrated pubescent feelings[2] in short lines that tumble over one another, while by the final section, “Very Very Agoraphobia,” the poems’ lines have grown longer (we even get a prose poem) and the speaker seems more self-aware.

But back to 1993, the year of the rooster. While I wouldn’t argue that PAUSA takes place in 1993 per se, the specific year doesn’t matter — the point is that 1993 is in the past, and is distant enough that one can be wistful about it. Substitute a similar year from your own life, say the year you turned seventeen, and the effect will be the same. What do you feel when you think about the year you turned seventeen? Nostalgia? Regret? Some mixture thereof?

To wit: the opening lines of “What I Mean is Yes” are a perfect encapsulation of much of the book’s project:

if I knew a girl who liked Superchunk

as much as I do I would buy her a record

player & a chocolate malt & a yellow house

in Pekin IL I would try to sleep with her

so together we’d dream the same dream

about moon pies & lightning bugs

that explode like popcorn in the summer

heat but goddamn I hate the summer

the air is matchheads makes me feel

so transparent tape so meth & unwound

baseball string my head is gin & vermouth

the morning after senior prom but

isn’t that a wonderful feeling I’m ready

to go dancing I’m ready to cut my neck

In addition to dealing with nostalgia head-on, one of Panic Attack, U.S.A.’s strongest qualities is its appropriation of a seemingly immature teenage voice, and how it uses what could be a thin, reedy, irritating whine to gracefully address a number of “big” topics. As Peter Markus says in his introduction, many of the poems in PAUSA tell us what it means to be “alive and thunderous inside a body and a skin that cannot contain the largeness and the wildness of the human heart.” And to quote Slawson himself, from his acknowledgements, this book abounds with “anxious love.”

1. with references to Michigan; Detroit; St. Louis; Lake Michigan; Cairo, IL; and a number to Kentucky, which isn’t really the Midwest but isn’t really the South either.↩

2. which brings to mind LCD Soundsystem’s “Sound of Silver”: sound of silver talk to me, makes you want to feel like a teenager / until you remember the feelings of / a real live emotional teenager / then you think again.↩

Sarah Rose Etter | Tongue Party

Caketrain, 2011

by Ursula Villarreal-Moura

In 2010, Sarah Rose Etter won Caketrain’s Chapbook Competition with her collection of unusual and provocative short stories. Three years later, Tongue Party is celebrating its third printing. Comprised of eight stories, these linked narratives trace the disintegration of an outwardly normal family into a cast of dysfunctional individuals.

In 2010, Sarah Rose Etter won Caketrain’s Chapbook Competition with her collection of unusual and provocative short stories. Three years later, Tongue Party is celebrating its third printing. Comprised of eight stories, these linked narratives trace the disintegration of an outwardly normal family into a cast of dysfunctional individuals.

“Koala Tide,” the opening story, is anchored in seven-year-old Cassie’s point of view. Recounted in laconic, childlike language, it details her parents’ blatant denials of an impeding coastal disaster. Their lies, however, can’t guard her for long. The reality of what the tide delivers is so gruesome and memorable that the ocean will never again be Cassie’s playground. “Koala Tide” serves as a springboard for the remaining seven stories, which delve deeper into Cassie’s initiation into adulthood, her fantasies of revenge, and her eventual martyrdom.

The stories in the first half of the book highlight Cassie’s loss of free will, first when she’s pimped out by her father in bars, then when she’s sadistically coerced into eating cake at the hands of her taskmaster husband. These men delight in controlling her movements, profitability, appearance, and by extension, her sexual identity. The harrowing narratives are marked by Cassie’s initial willingness to please and her assertion that she consented to this barbarity by being present, or by vowing to be a wife. “I agreed to this by showing up,” Cassie ominously confesses in the titular story.

As the collection progresses, the reader learns that Cassie’s father does not, with time, fare well either. After a family tragedy, he seeks solace by hiding out in a chicken mask. In a karmic twist, the man who exposed his young daughter to too much too fast begins to smother himself with a potentially toxic plastic mask. While Etter doesn’t go so far as to suggest schadenfreude, the irony of his pitiful state is unmistakable, yet the father’s newfound vulnerability evokes unexpected emotions as well.

The crown jewel of the collection is the titular story “Tongue Party,” which blends the past and present, control and chaos, family and strangers, innocence and corruption. Given its creativity and precision, it’s easy to hold the other stories to this exceptionally high standard. In comparison, the penultimate piece, “Cures,” employs a poetic stanza structure, making it too abstract and inaccessible. Likewise, “Husband Feeder” rings too predictable given the thrilling surprises of “Tongue Party.” At their best, Etter’s brief stories invite the reader to inhabit crevices of cruelty and tenderness, and to re-examine the usage of common words like party and marriage.

In “Men Under Glass,” the narrator, clearly fed up by the course of her life, decides she will call the shots from now on. A natural in bars, she challenges the familiar dynamics of attraction when she captures men, takes them home, but doesn’t give what they expect at the end of a lustful night. “In my house, things move the way I want them to,” Cassie asserts before following through with a new set of rituals. While the reader will likely appreciate Cassie’s seizure of power, not all change is permanent. The final story, “Husband Feeder,” in which Cassie sacrifices herself completely to her husband, ends as expected. The struggle is over before it begins. Like Donald Barthelme’s “The School,” “Husband Feeder” is extreme in scope. Whereas in Barthelme’s story, the students are exposed to the cycle of life time and time again, Etter’s story offers Cassie relief in “waves of blue,” an echo to the beginning, before the koalas, before there was reason to mistrust adults and fear the ocean.

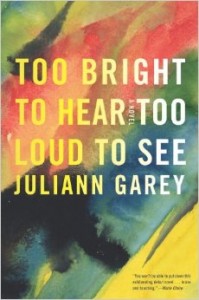

Juliann Garey | Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See

Soho Press, 2012

by Brian Gebhart

As I was reading Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See, it occurred to me that Tolstoy’s famous line about happy and unhappy families could fairly be extended to people’s minds: while all the healthy ones are pretty much alike, each unhealthy mind is unhealthy in its own way. Regardless of the particulars, some people’s minds are certainly more difficult to inhabit than others. And as the title of Juliann Garey’s first novel suggests, Greyson Todd—who tells his life story in a collage of memories that pass through his brain as he undergoes electroconvulsive therapy—is burdened with a mind of the difficult-to-inhabit variety.

As I was reading Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See, it occurred to me that Tolstoy’s famous line about happy and unhappy families could fairly be extended to people’s minds: while all the healthy ones are pretty much alike, each unhealthy mind is unhealthy in its own way. Regardless of the particulars, some people’s minds are certainly more difficult to inhabit than others. And as the title of Juliann Garey’s first novel suggests, Greyson Todd—who tells his life story in a collage of memories that pass through his brain as he undergoes electroconvulsive therapy—is burdened with a mind of the difficult-to-inhabit variety.

Of course, a person’s family plays a critical role in determining what kind of mind one ends up with. “I do not believe in God,” Greyson remarks at one point. “Instead I believe in the power of Family… God, for example, can’t give you an excellent head of hair. Your family can. They can also give you cancer. And heart disease. Nothing kills like Family.” Greyson’s unfortunate inheritance is severe bipolar disorder, which his father also suffered from. Growing up in a household plagued by mental illness gave Greyson a close-up view of the mania, depression, and psychotic episodes he would experience as an adult. When his own affliction begins to manifest itself in early adulthood, Greyson copes with it by alternating between cycles of secretive treatment and outright denial. A powerful executive at a major film studio, he knows that living openly with his affliction would probably cost him his job. But after twenty years of wrestling with the disease, trying to achieve a happy life by sheer willpower, Greyson gives up. He decides that the best thing he can do for his wife and daughter is to leave them, and he spends the next decade wandering the world. He’s amassed enough savings to travel from Israel to Chile to Uganda and many points between, skipping town whenever his behavior causes too many unsolvable problems.

The novel’s structure is similarly peripatetic, jumping among times and places with the associative quality of our narrator’s fractured memory. As a character, Greyson is most interesting during moments of comparative stability—the scenes from his childhood or the episodes when he’s lucid enough to regret the loss of his former life. The sections detailing Greyson’s world travels are fast-paced and overstuffed with incident, often veering toward exotic clichés (a teenage seductress he meets in the Negev desert, for instance, strains credibility). And at first, these scenes almost appear to glamorize his illness. But Garey, who has edited a collection of essays about bipolar disorder, is clearly aware of this dilemma. At a hotel in Bangkok, as Greyson watches a beautiful young woman emerge from a swimming pool, he realizes that he’s “been filming her—this scene—in slow motion. I am disappointed in myself. Such a cliché. Such an obvious choice. But then Bangkok itself is a cliché. I knew that and I came anyway.” Greyson can’t seem to find pleasure in anything uniquely his own, because anything he touches will end up corrupted by his disease.

The strongest moments in Too Bright to Hear Too Loud to See are the quietest ones. A scene late in the book finds Greyson living in New York, his only friend an elderly neighbor, Walt, who lives in the same building. On a visit to his apartment, Greyson notices that Walt has a collection of his grandchild’s construction-paper artwork hanging on the fridge. Desperate for some connection to his own estranged daughter, Greyson nearly breaks down in Walt’s kitchen, then steals a “macaroni-and-lentil collage in the shape of a heart” and takes it home with him, revealing that even though he’s deserted his family, they remain the center of his existence.

So, while happy families and healthy minds are both in short supply in Garey’s novel, hope is not entirely absent. As Greyson finishes his electroconvulsive treatments and begins the long, arduous process of piecing his mind back together, family—with all its blessings and curses—remains the one constant force in his life, as well as the most powerful reason to keep striving for happiness.