An Interview with Shawn Huckins

by Jeff Simpson

by Jeff Simpson

August 1, 2011

I was first introduced to Shawn Huckins after seeing his Paint Chip Series featured on The Jealous Curator (a kick-ass art blog if there ever was one). The Paint Chip Series features several large canvases painted to resemble the color swatches you’d pick up at Sherwin Williams before covering your living room in Pacific Sea Teal. Each “chip” also incorporates some mundane image drawn from the everyday—a Walmart employee pushing shopping carts across a Sweet Corn landscape; cars sinking into a Honey Beige flood. Huckins’s work is polyphonic, operating on several modes at once. The work is clever, sure, but it’s also deft.

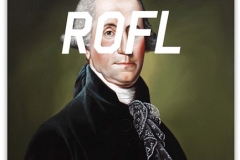

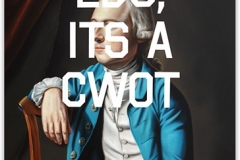

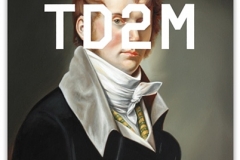

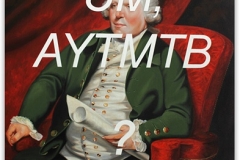

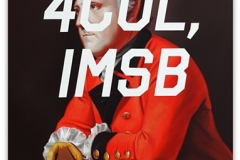

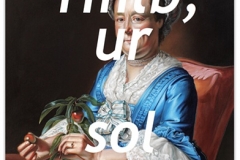

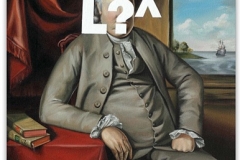

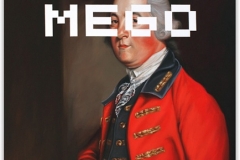

In his latest series, American Revolution Revolution, Huckins painstakingly replicates 18th century portraits from the American Revolution and then superimposes text-messaging acronyms in large white letters. The result is a deeply interesting mix of pop-cultural humor and postmodern theory that toys with the big questions: Have we reached the Baudrillardian point where hyperreality has supplanted nature? To what extent do text-messages and Facebook posts further destabilize meaning and language? And underneath it all lies a sharp sense of humor and a juvenile assertion that we shouldn’t take any of it too seriously.

Shawn Huckins was born in Laconia, New Hampshire. In 2005, he received a degree in studio arts from Keene State Collage. He currently lives and works in Middletown, Connecticut

The Fiddleback: How did the idea for American Revolution Revolution first come to you? It seems like the kind of thing that might start as an inside joke and blossom from there.

Shawn Huckins: Just like chocolate chip cookies, it happened by accident. The initial step was a challenge brought indirectly by my cousin who called me out and said that I was very skilled at painting most things, most things except faces. And he was right! In my early work, I would always place an object that blocked the entire face because I was intimated by painting a face or any anatomical feature that revealed flesh. To prove him wrong, I started to practice by copying 18th century American portraiture because the faces were painted in a way that I found traditional, realistic, and monumental. Plus, I have an obsession for that time period in American history. Of course, the first few dozens were garbage and I would place them aside in pile and start another. One of the paintings that I threw out happen to land under a piece of tracing paper that had the acronym “LOL” written on it and beneath that piece of trace, you could see the crap reject painting. Seeing that sparked an idea of not only how neat that looked visually, but also the juxtaposition of two completely different worlds—one that relies on hand written letters, formal communication, and a civil way of life versus our technology driven, priorities in the wrong places, obsessed with Snookie kind of society. So I started painting text acronyms over the parts of the face I could not get right or got too frustrated with and it just evolved into something much greater. I like to think my face painting skills have grown since I started, and now I’m a little more confident to reveal more and more of the face.

The Fiddleback: For me, the series raises several questions about technology and the nature of communication without polarizing the argument. On one hand, the superimposed text on portraits of Washington turns the joke on us because we’ve supplanted great documents and stately papers with shorthand (arguably meaningless) acronyms. On the other, it asks us to consider what Washington and other historical figures whom we’ve overly mythologized would say if they had iPhones and Facebook accounts. What’s your take on all this and technology in general?

SH: Technology is great! I love it and couldn’t live without it. It has helped millions improve their lives (medically and educationally) and has also made it easier for people to stay connected and current. But also, technology can be very obsessive, time consuming, and sometimes just irritating. It makes you wonder what life would be like without the cellphone, the iPod, or Twitter. One can only dream…or move to a distant island. I see the younger generations (and I’m totally in this crowd) become more grammatically illiterate and less interested in learning how to communicate properly. Although it’s very easy to stay connected with anyone anywhere, we ironically seem more removed from each other and far less personable. I only have a Facebook account which I check once per month where I spend some time looking for strange or new texting acronyms to use in my work. With Twitter I feel a tremendous amount of pressure to be funny and/or witty, so I just avoid the whole sha-bang.

The Fiddleback: Explain more why you chose this period of American history. Are you a history buff?

SH: I’m a history buff only when it comes to this time period thanks to a field trip I took in fourth grade to the Freedom Trail in Boston. Ever since learning about the stories of Paul Revere, The Boston Tea Party, or Washington’s Delaware Crossing, I’ve had a slight obsession with this time period—the way they lived, the architecture, the tools, the artwork, the uniforms, the Fife and Drums, the formalities. This was a time when our nation was getting its ass in gear and forming a nation that will eventually become the United States of America.

I have researched some of my subjects, for example, in “The Wig Maker’s Re-Post To Fat Taxation,” the wig maker’s name is Richard Arkwright, who was famous for his ample girth and was also the richest man when he died. But rarely do I incorporate their personal backgrounds with the story of the text; I mainly go for composition and effect when choosing my subjects.

The point I was trying to portray is that Americans, on certain levels, have their priorities in the wrong places, priorities that seem to blind us from what’s most important.

The Fiddleback: Are you interested in typography? Most of the messages differ in font—do you think the aesthetic shape of our words affects how we communicate or what we choose to communicate in the first place?

SH: The first paintings in the series use the font Octin College (as seen in GW’s Comment or Montresor) which the only reason why I chose that type face was they were very easy to mask off for the taping process to protect those areas from layers of paint used for the portraits. It was also bold and almost distracting, which I liked because texting/phones can be huge distraction, so the message behind it was relevant too. As I progressed I wanted to match the fonts used on cell phones or on social media sites to make it more of an authentic “text.” The majority of type faces on FB, Twitter, or on iPhones for example, are Arial, Trebuchet MS, or Times New Roman. I also played with italicizing the acronyms in several paintings to give it more of a softer tone of a statement instead of a straight hard-edged message.

The Fiddleback: According to your bio, you’re a huge fan of Edward Ruscha, who was raised in Oklahoma City (current location of Fiddleback HQ.) What is it about Ruscha’s work that moves you?

SH: Ruscha’s randomness and his combinations of words and imagery is just fascinating to me. Also, seeing his work in person is just so breath taking….they are massive. I went to the Whitney not too long ago and on the third floor they were hosting an exhibition of a prominent collector’s art collection. As soon as the elevator doors open, or you come to the top of the stairs, you are immediately presented with a very large Ruscha painting with text sprawled across a sky of oranges, reds, and yellows. His messages within the work are so random, almost mundane, but come across as witty and comical. I’m drawn to a lot of artists within his genre because the seriousness is almost absent and I enjoy work that doesn’t have some incredibly deep meaning or make you want to drink heavily afterwards.

The Fiddleback: For me, “Portrait of the American Gentleman” is one of the more provocative pieces. It connotes the phrase, can’t see the forest for the trees, as if he’s blinded by the idea of America itself. Is that how you see it?

SH: A few people found this painting offensive, which I totally get. Taking an American flag and basically creating a blindfold, something terrorists have be known to do with their hostages, certainly evokes a certain “disgracing the flag” tone. However, disgracing the American flag was/is never my intention. The point I was trying to portray is that Americans, on certain levels, have their priorities in the wrong places, priorities that seem to blind us from what’s most important. What is important will vary from person to person, but what’s important to me is not to lose site of traditional ways communication, helping out a neighbor in need, baking an apple pie from scratch, or learning to pull our faces away from our social media.

The Fiddleback: On average, how long does it take to complete a portrait? Did you get the foam insulation wig perfect the first time? If not, did you have to practice making foam insulation wigs?

SH: Paintings range on time spent based on how detailed the work is and how large it is. Most paintings take on average of a few weeks, but some can take months. After the underpainting is complete, I always work on the hardest parts first to get them out of the way—face, hands, etc. As for the wig portrait, that came after several trial and error runs on plywood. I knew the exact shape and size I wanted to make the wig, so I drew several copies on plywood and tried the foam spray on those, concentrating on pressure of the trigger, my speed, etc. Once I felt confident that I wouldn’t screw it up, I went ahead and did the real thing and thank goodness, it came out flawless because it’s a real pain to manipulate the foam to your liking after it’s applied.

The Fiddleback: As I mentioned before, your work raises questions about various cultural systems—language, technology, history, etc. Given that most artists and writers use college to hone their craft, what’s your take on academia as a cultural institution of art?

SH: I’ve heard many stories of artists who complete a degree in the arts field and end up working in the painting section of Home Depot, the photo lab at CVS, or not in the field whatsoever. And that’s not just for art majors, it goes for many graduates who get degrees in one subject and make a living off an entirely different field. I have been very lucky to find work within my chosen degree. Once I graduated college, I got a job as an architectural model maker/painter, and I’m currently an artist assistant for another artist, so I’ve been fortunate to be constantly submerged in the art world. Of course, I would love to go independent, but that takes years of hard work, patience, and a thick skin. College (especially an MFA program) is a personal choice, and I believe it can develop your ideas and theories and give you a very open perspective on how to create, but I also think that some people just have it, or they don’t. Years of schooling can give you the knowledge of art basics, but having that natural born talent is definitely a huge benefit.

The Fiddleback: Besides other artists in your field, who/what influences you?

SH: Not sure of influences, but what motivates me is this weird physiological urge to be super successful and prove to my family that I can be make a living as an artist. I know they will support me in anything I choose to do, but I have this need (maybe to prove to myself) that I can take this talent and make something of it. I have a lot of drive. I also enjoy seeing other much more talented artists succeed and studying their “success blueprint” of how they got to where they are now; meaning, what places they’ve shown, what awards they’ve won, or what collections they’ve been in. There’s also a need for me to see the work up close and try to figure out how they did it, or get hints of their techniques, which in turn is very inspiring.

The Fiddleback: What’s in store for your next project?

SH: I honestly haven’t thought that far ahead yet. I’m enjoying what I’m currently doing, however, I would like to take it a step further and possibly work in some more monumental pieces, not only portraits, but also landscapes and possibly battle scenes from the American Revolution with current day lexicons superimposed on top. First though, I need a bigger studio.

——–

Shawn Huckins