An Interview with Jim Denomie

by Benjamin Davis Brockman

April 1, 2013

In a 2005 radio interview with mnartists.org, Jim Denomie described his new understanding of creativity following his “Painting a Day” project. Worldly concerns and those in the studio make for two separate lives for many artists, especially those who work full-time to support their artistic practices. And while time and other practical matters may mean that the two lives are like oil and water, Denomie’s daily painting ritual opened a new passage to the creative plane, proving that time is like any other resource. As any great artist, Denomie learned to do a lot with a little. However, the way Denomie describes the bridge between these two worlds is the visual narrative of an artist who has one foot firmly planted in our common rat race and the other deeply embedded in a colorful, spiritual place. As he sees it, this is not his place alone, but the place that all artists access in forging their creative spaces:

I began to see this visually. I saw it as a two-part composition. The lower part being the reasonable real world, and the upper part being the creative dream world. And down in the lower, reasonable world there’s an artist on his hands and knees sticking his head into an oven, and he’s reaching up and turning the gas on full blast. And from the back of this oven is the smokestack going up to the creative world, and to get there it’s gotta go through a macaroni and cheese membrane. And then when it gets to the creative world it comes out in this volcano-like form and this guy’s head is coming through the top of this thing, and he’s just up and looking at the sky and he’s just amazed at all the beautiful colors and the Picassos and Van Goghs and the Frank Big Bears and the Jim Denomies flying around up there, and all kinds of weird birds and fish and animals that are part human and part fish or whatever. Just these really, really cool places up there, and he looks around and there are other volcanoes and other heads popping up there, and it’s the creative universe that all artists go for their material.

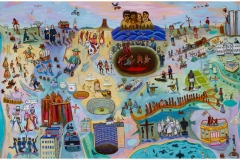

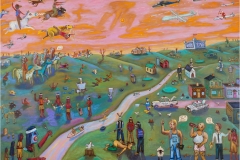

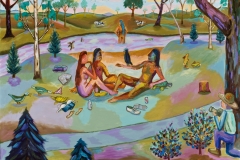

For anyone familiar with Denomie’s work, it might not be hard to picture what such a painting might look like. His colorful narrative landscapes are rife with character and personality and loaded with symbolism and humor. In larger works, his stories span the history of Native American culture, punctuated with relevant contemporary pop imagery, bridging a generational and cultural gap with vivid color. And while the word “naïve” has been used in association with his work, it could certainly never be in the pejorative sense. Denomie is an academically trained artist with a singular spirit, which stems from as much from his self-training and dedication to creative growth as any institutional criteria. Here again, Denomie seems to have his feet planted in two separate art worlds—one which bears resemblance to folk art with flattened perspective and simplified forms, and one rich with an understanding of color and a clear mastery of storytelling. Far and away, the stories Denomie focuses on—those of his native Ojibwe culture, cultural divides, and political disgraces—are what most compel the eye of the viewer to study his works. And these studies prove endlessly rewarding.

The Fiddleback: You have mentioned before that the use of pop symbols is one way of carrying meaning from one culture to another. Do you find this is true of generations as well? What role do these divides play in your life, creative or otherwise?

Jim Denomie: Being a Native American male with a mainstream art education, I compete in both mainstream and contemporary native art arenas. I often use images of pop culture to help tell stories that both native and non-native people will understand, to varying degrees of course. My intended audience is everyone, young and old, present and future.

The Fiddleback: Your work has been described as “revisionist” in its approach to depicting Native American history. Do you think your stylistic choices are deliberate in giving voice to obscure history? What is your process like in setting out to tell a story such as that of Non-Negotiable for instance?

JD: I would like to think that when they say “revisionist” they are talking about seeing things in a different way. I am trying to comment about issues from my point of view as I understand them. I am not trying to re-write history. I am not creating history. I am just bringing more of it to the surface and presenting it in an honest way that is more appealing and less alienating. Often, I use humor to diffuse a tense situation. Because of some of the historical events of this country’s development, sometimes that humor can be sarcastic. Non-negotiable was commissioned by Tilly Laskey, the former curator at the Science Museum of Minnesota. She told me that she liked the way I commented on history and asked if I would be interested in doing something about Bishop Whipple. I did not know of Whipple so I had to do some research on him. I discovered that he played a prominent role in an event that I was more familiar with, The 1862 Dakota War or Sioux Uprising. Once I learned that he was an advocate for the Dakota people before, during, and after the uprising, I had some ideas about how I was going to compose the painting.

To someone who is serious about becoming a successful artist, I would say define what success means to you. If it is selling, making a lot of money, I would say good luck.

The Fiddleback: What are your greatest influences in your work—from art to daily life? How much overlap is there between your personal and creative life?

JD: My work comes out of me, who I am, through my dreams, my imagination, and my memories. Dreams and imagination are similar, but different: one is sleep dreaming and the other is daydreaming. My memories come out of my intelligence, education, and personal history. I would say that the greatest influences on my work come from those that teach me, my painting instructors at the U of M (University of Minnesota), the animals, the clouds, my family, cultural identity, politics, history, my environment (physical, cultural, spiritual), generally the world around me. There are many artists whom I admire greatly, but I feel most provide a source of inspiration more than a conscious influence. I would say that aspects of some of my paintings relate to the lyrics of songwriters Bob Dylan and Paul Westerberg, but I would not call them influences.

The Fiddleback: What was the Painting a Day project like for you? I see some repetition of images or scenarios, such as the Indian and Cowboy exchange which occurs in Eminent Domain and elsewhere in a smaller work, You lied to me. Get used to it. Again the scenario appears with the Indian telling the Cowboy to “Pull my finger.” Is that recurring phenomenon in anyway related to the daily work?

JD: The Painting a Day project was phenomenal. I gained so much in one year. First, I told myself that this exercise was going to be about experimenting, exploring, and playing. I wanted to go back to my Jr. High art classes where there were no expectations, no destinations, and just have fun. I also had a goal to learn to paint more expressively like Joan Mitchell, Nathan Olivera, Elmore Bischoff and others. Immediately, I started to wow myself with these small creative portraits and their unexpected results. Through the course of doing at least one painting every day for the entire year, I experienced several revelations and made a breakthrough in developing a new painting style. I would have to say that the repetition of symbols and scenarios in my work is not really related to the daily painting project. I sketch quite often, capturing ideas and thought fragments that frequently become paintings and/or episodes in larger paintings. Some become a series, like the Indian and Cowboy you mention are part of my Tonto and Lone Ranger series.

The Fiddleback: There is a comic strip quality or graphic novel style to some of your narratives, though the image plane often flattens perspective to tell a very complex story in a single work. What influenced these larger narrative landscapes?

JD: I cannot point to a definitive influence on the larger narrative landscapes. I believe that they are the current results of the continuing evolution of my work. Casino Sunrise is the third rendition (of 3) of the MN State Seal, which, at 50×70”, is the largest of the three (Show me the Money, 18×24” and Hole-in-the-Day, 35×49”). While working on Eminent Domain, A Brief History of America, 84×144”, I thought to look at Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. I am not sure what I took away from that viewing since a lot of the imagery for Eminent Domain already existed in sketches and in my mind. To me, Garden of Earthly Delights has a kind of fairy tale feel to it while I wanted to tell a story about history and truth. I guess I was looking more for compositional ideas. But I am still not sure if and how Bosch’s fantastic painting may have influenced the final image.

The Fiddleback: Your work seems political and spiritual in equal parts. Do you see these agendas as separable?

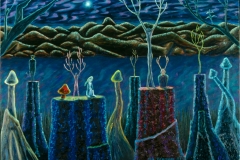

JD: I would add sexual to the list. I think they can be separable agendas but often they overlap. Some of the moonlit landscapes like The Visitors are more intuitive, mostly spiritual and somewhat erotic, whereas I see Split Decision and Casino Sunrise as political paintings with humor.

The Fiddleback: Can you talk about the Wabooz imagery? It seems to manifest itself in a vast majority of your work, but its meaning is shaped differently by context throughout. I have frequently heard you associate it with dreams, which I gather are tremendously influential in your creative life. But in Non-Negotiable the rabbit appears rather subtly, burrowing up from the soil, celebrating the re-emergence of the Chilean coal miners (following the 2010 Copiapó mining accident). Is metaphor frequently generated by such associations?

JD: I have been aware of a special connection with the rabbit since I was a young person. I find that it is not necessary, for me, to define that connection, so I don’t. Sometimes, rabbits are the main subject matter and sometimes I place them in a painting to assist in a story. Often, they are just bystanders. And sometimes, they appear unintentionally in the brushwork. I frequently use metaphor as a tool in my narrative work. When working on a painting, I often will put in something to reflect what is happening in the real world around me. As was the case of Non-negotiable and the rescue of the Chilean miners, I try to be original and creative when using metaphor to convey a message.

The Fiddleback: There seems to be a big shift between your earlier work with the mesas and flying horses to the more recent works. Both contain deeply spiritual elements of the surreal, but was there anything that changed for you?

JD: I believe my work changed considerably after completing the daily painting project of 2005. During that year, there was little focus on any of my previous narrative work like The Renegade series and Dream Rabbit series. After the daily painting project, I felt that I had developed and evolved as a painter and felt a challenge and a need to continue my social and political stories in a new style. I believe that the biggest change was this colorful abstraction of forms and landscapes (people, animals, fish, birds, clouds, trees, etc.) that some call Naïve or cartoonish. (I have to say here that I have never felt cartoonish was an appropriate description.) The social and political content of my Renegade series survived and is now presented in a more generalized abstracted landscape—the same landscape where I can also portray my humorous, spiritual and erotic content, in stories that are all somewhat cohesive, in a similar form.

The Fiddleback: How do you respond the terms like “naïve,” “folk” or “outsider art?” I’ve been told that I can never really be an “outsider artist” because of my academic training. And although I have no desire to encroach on folk artists or to cheapen the phenomenon, I feel like it is very much a spirit, not a matter of form or technique. What role has your education played in shaping you as an artist?

JD: I agree, outsider, naïve, and folk art is just a classification of artists that are still artists […] who make art mainly for the sake of making art. There is a spirit to their approach and production that I am attracted to. Clementine Hunter said, “God didn’t say rich. He didn’t say famous. He just said paint.” Recently, I pulled out the book Painting by Heart and studied her work because I thought some of my recent paintings were drifting in her direction. I have a profound admiration and respect for a number of outsider artists as well for children’s art. Even though I am a trained artist, I relate to the outsider artist. I am just an old fashioned painter, using paint, brushes, and canvas. I do not participate in the current conversations of art movements nor am I able to.

The Fiddleback: What effect has sobriety had in your creative life? For instance, many people cite substances as integral in their artistic pursuits, but I have found that my creativity and drive flourish in sobriety.

JD: Since I have been sober (24 years) longer than I have been making art (seriously) I would say sobriety has been very good for my creative spirit (as well as my physical and mental health). I knew when I was very young that I wanted to be an artist and eagerly participated whenever it was offered in school. But when a high school counselor would not support my wishes to pursue art (this is the short version to an important story in my life) I quit school at age 16, got into a life of partying and addiction for the next twenty years, and I gave up art. I got sober in 1989 and enrolled at the U of M the following year hoping to get into the Health Sciences program and out of construction. But after taking a drawing class, I changed direction, and in 1995 I graduated with a BFA in visual art. And the rest is history.

The Fiddleback: What advice would you give a young artist or any person who strives for a successful creative practice? What inspires you to keep going?

JD: To someone who is serious about becoming a successful artist, I would say define what success means to you. If it is selling, making a lot of money, I would say good luck. If success means recognition in terms of grants and awards, museum shows and collections, publications, I would say, create work that is honest, bold and daring, to keep evolving and exploring, and most important, exhibit. Show your art wherever and whenever, in the beginning. To me, exhibiting is as important, if not more than, selling. In my career, I have found that one opportunity has led to two more. What motivates me to keep going? I still have ideas. I still have aspirations. I am still having fun. And what motivates me most is time. At 58, I am hoping to live and to work in the studio until I am 75. (Because Native American males have the lowest life expectancy of any group in this country, I think that is a reasonable goal). Anything beyond that will be a bonus, but 17 years is not a lot of time.

The Fiddleback: I love your description of the way you have visually described the creative realm as distinct from the practical. If you had to draw a picture of your muse, what do you think that would look like?

JD: I am not sure, but it would probably have tits and wings.

——–

Jim Denomie

1. Non-negotiable – 40×56″ (2012)

2. Eminent Domain, A Brief History of America – 84×144″ (2011)

3. Casino Sunrise – 50×70″ (2009)

4. Off The Reservation – 72×96″ (2012)

5. Edward Curtis, Paparazzi-Skinny Dip – 40×56″ (2009)

6. Attack on Fort Snelling Bar and Grill – 35×49″ (2008)

7. End of the Trail – 36×24″ (2008)

8. Visitors – 24×36″ (2012)

9. Transitions (from the Renegade series) – 35×49″ (1997)

10. Dream Rabbit III – 32×49″ (2001)