An Interview with Jamie Kinroy

by Benjamin Davis Brockman

by Benjamin Davis Brockman

April 1, 2012

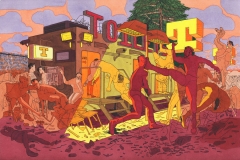

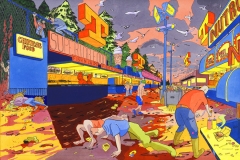

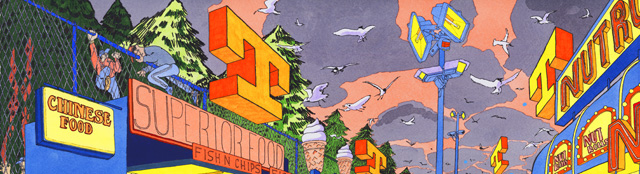

Scottish artist and DJ Jamie Kinroy’s drawings survey a modern American landscape dotted with junk food wrappers and pop cultural icons. He distills our conventional excesses, our densely packed horizons, into almost sickeningly vibrant narratives forced into rigid lines and complex perspectives as seen through the eyes of a keenly observant club-goer. While his work may fit nicely into a retrospective of The Hairy Who with his verbose “colour” combinations and absurd “humour,” his imagery draws from the whole of our modern way of life. Kinroy thrives in the ruin of urban collapse. He shows a startlingly realistic view of our current state that’s coupled with eerie depictions of what our future may resemble. His interests are extremely broad, ranging from electronic music and video games to science fiction and junk food. I invited him to talk about the self-described “virtual junk food” that inspires his work as well the actual junk food in his graphic oeuvre.

Scottish artist and DJ Jamie Kinroy’s drawings survey a modern American landscape dotted with junk food wrappers and pop cultural icons. He distills our conventional excesses, our densely packed horizons, into almost sickeningly vibrant narratives forced into rigid lines and complex perspectives as seen through the eyes of a keenly observant club-goer. While his work may fit nicely into a retrospective of The Hairy Who with his verbose “colour” combinations and absurd “humour,” his imagery draws from the whole of our modern way of life. Kinroy thrives in the ruin of urban collapse. He shows a startlingly realistic view of our current state that’s coupled with eerie depictions of what our future may resemble. His interests are extremely broad, ranging from electronic music and video games to science fiction and junk food. I invited him to talk about the self-described “virtual junk food” that inspires his work as well the actual junk food in his graphic oeuvre.

The Fiddleback: Can you tell us a little bit about growing up in Scotland?

Jamie Kinroy: I was born and raised in Edinburgh in Scotland and spent a lot of my childhood reading manga, watching cartoons, playing video games, and drawing pictures and comics. I also loved playing with fire and fireworks, blowing up dog turds and stuff. Most of these hobbies I have continued to enjoy.

The Fiddleback: How did you find yourself pursuing the arts as a professional endeavor?

JK: When I was about ten, my dad took me to the Edinburgh College of Art ‘Degree Show,’ where I saw lots of animations, paintings and illustrations. Someone had made this installation where they constructed a living room out of ‘bits’ of pig. The furniture was all fashioned out of pigskin with the hair still on it, and the feet of the chairs were made out of trotters. There was a chest of drawers where each drawer handle was a pig snout. From that day on I knew that I had to be an art student, and sure enough, once I made it through primary and secondary school, I ended up at Edinburgh College of Art. I was going to go into illustration, but decided on painting—my reasoning being that I’d rather illustrate what was in my imagination […] than some stuff someone else had come up with. While I was at high school I listened to a lot of trance on my headphones and became an electronic music enthusiast. By the time I got to art school I was listening to Detroit Techno and started DJ-ing at my friends parties and clubs and things. I finished art school and painted in my bedroom for a while before moving to Minnesota to seek an MFA.

The Fiddleback: Your description of your work as a mixture of Edward Hopper and Grand Theft Auto—or Frank Miller and JG Ballard—rings remarkably true. What other inspirations do you draw from?

JK: love computer games. I draw from computer games a lot. Of course, as a response to, and a simulation of, life in a big city, you can’t beat Grand Theft Auto. My favorite was San Andreas—set in a blocky and lurid fictionalized version of California. But I also take influence from games like LA Noire, the Hitman series, Deus Ex, Resident Evil and older games like Streets of Rage for the Mega Drive. Most of the Streets of Rage games I see as working within this area of visual culture that deals with these gritty, dystopian urban environments, quite like cyberpunk. In almost all of them, you end up in a corporate skyscraper, battling street punk minions all the way to the top floor, where you have to take on the boss, a colossal, […] suit-wearing fat-cat CEO type, who usually is really good at fighting or will have some sort of machine gun. I love those games. I like the way they re-imagine urban environments, especially corporate architecture and their extravagant office spaces as these futuristic battlegrounds. JG Ballard does a similar thing in his novel High Rise, another big influence.

In a more general sense the (real) urban environment provides me with endless inspiration. I take photos of everyday, mundane commercial and residential architecture. Cars, industrially designed objects, like office furniture, and plastic coffee shop chairs. And chain link fences, modern urban forms like concrete structures, parking meters, traffic lights, signage, strip mall architecture. These things and the way they are arranged I find strangely exotic when closely examined.

The Fiddleback: You recently moved to the US from Scotland. So much of what you address in your work are American motifs or phenomena. Has moving to the States shaped your aesthetic or informed your content?

The Fiddleback: You recently moved to the US from Scotland. So much of what you address in your work are American motifs or phenomena. Has moving to the States shaped your aesthetic or informed your content?

JK: Yes! It’s really weird! I hadn’t visited the US until I won a travelling scholarship while at art school and went to Kansas. I have always been fascinated by American culture, and so the first time I came here was a brilliant and exhilarating experience. It was also surreal. Because of this globalised world we live in now, much of the visual culture and urban landscape of the US was (obviously) already familiar to me. Of course this familiarity was mainly from my contact with it through films and computer games. The experience was, and continues to be, something akin to living in a computer game, like that film Tron. It’s awesome!

In terms of my work there’s just so much visual material here that’s freaking fascinating. I love riding around on the light-rail trains here in Minneapolis, taking pictures of everyday architecture, even just hanging around in parking lots is great! There’s just an infinite amount of “stuff” here that has already [informed] the content of my work. Strangely enough it’s made me think about location in my worlds (work)—where are these places? It’s led me to draw more Scottish or UK “stuff” than I did before, mixing it with what I find here…I want them to be these weird combos, strange non-places that are everywhere and nowhere, as that’s really what the world is like these days, isn’t it?

The Fiddleback: What is it about living in a city that inspires you creatively, and how does that differ from your experiences in Scotland?

JK: It’s the complete and utter saturation with information. When I was around 10 or 12 or something, my Dad showed me Blade Runner, which fundamentally shifted the way I perceived urban environments. It’s the quintessential city film: a visionary stylistic collage, which appropriates elements from a multitude of different eras and cultures, reflecting information overload and a loss of history and location in modern cities. It’s science fiction, but it’s speaking to things, which we are experiencing right now! Ever since seeing Blade Runner, the layers, depth and complexity of urban worlds have been an endless source of fascination.

I’m drawn to urban dystopias, and bleak manmade landscapes: synthetic materials and plastics, discarded junk food packaging, advertisements, billboards and concrete structures, machinery and urban electronics, surveillance cameras and drones. I find a lot of beauty in the mundane, man-made and industrial. The contradictions interest me, the inherent ugliness opposed by the allure of delicious Day-Glo, neon and manufactured colors and forms.

The Fiddleback: Is there a connection between your love of music and your drive to create visual works? Do you see being a DJ and being an image-maker as exclusive of one another?

JK: No way! Listening to music plays a huge role in image making for me. I realised this early on. I spent my undergraduate degree drinking coffee and listening to techno while drawing—it was great! After I graduated I couldn’t find a job so I just painted/drew in a tiny room in my apartment in Edinburgh. I would stay up all night listening to slamming techno, drawing and drinking this stuff called “kick” which was a knock off of Red Bull made by a British retail corporation called Tesco. It was fantastic. I’d get to this point where my eyelids started to vibrate! I love the energy of techno, and I suppose the focus it demands. I suppose my drawings share some of the same attributes in their clinical nature and clarity; I guess it’s like the complete opposite of old school abstract painters getting wasted while working! I just like the futuristic and synthetic sound of electronic music. I think it goes well with my subject matter.

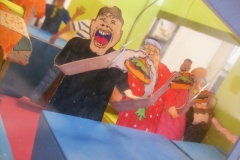

I’m interested by the strangeness of the whole culture of junk/ fast food…the packaging, fast food restaurant architecture, the oddness of the interiors…the eerie sort of “staged” formalities and routines that the poor employees or “team members” of fast food outlets are forced to participate in.

The Fiddleback: Your use of line and color in creating narrative is so deliberate and controlled. Is the proliferation of digital media an influence on your style? What do you think the digital age means for fine art?

JK: Digital media really interests me. I used to collect my source material from printed newspaper images and clippings from glossy magazines. I like video-game magazines and wrestling magazines and stuff like TV-guides and glossy commercial inserts… but these days I’m more collecting my imagery off of the Internet. I surf trash on the internet and download stuff or take screen-grabs; I have an enormous folder on my computer of imagery that’s come off the internet as well as my digital camera. I think right now there’s over 600 images in there, and that’s just my most current folder. I like visiting weird websites that you wouldn’t think to go to, like for fast food chains—there’s one in Canada called Chicken World that has a great website, with music and animations. Also in the UK we have Chicken Cottage, which used to have a fantastic website but they changed it. And so most of the time, I’m drawing from a computer screen! It’s a difficult translation sometimes. But I like that this has become part of my process. We have this sort of dependent symbiotic relationship with the Internet in the western world, where hours of our time just evaporate in front of screens. I like to think I’m reclaiming a piece of the Internet’s power over me by turning this vacuous “surfing” into something productive. Also it seems a pretty direct response to the idea of “information overload,” which I mentioned—a direct translation by hand from the screen to the paper.

Funny enough, I’m not a very technologically savvy person. I once tried writing my name with a Wacom tablet, and it looked like a five-year-olds signature, but by no means am I against or resistant to technological advancements. In fact. I’m all for them. I think it’s good for (some) artists to have all of the skills and tools of the technological cutting edge at their disposal. Their just tools aren’t they? People love to say this, about almost anything: “They’re just tools!” But on the other hand, David Hockney did those iPod paintings, which are boggin’ (Scottish word for ‘gross’) So I suppose it just depends what you do with it. I like people who are making digital collage. I like the idea of re-appropriating some of this commercial imagery we are bombarded with and making something subversive and visually striking with it.

The Fiddleback: Who do you think is making the best music right now and why?

JK: That’s tricky. I’m finding so much brilliant stuff right now. I just heard Araabmuzik’s album from last year called Electronic Dream, and I’ve never heard anything like it! He samples of all of this really cheesy trance music that I used to love when I was about 15 and slams these really killer hip hop beats over the top of it. It’s great! It’s super futuristic. Apparently he’s got another album in the works. I like Kuedo too; he did a mix for Fact Magazine last year, which blew my mind. I also like a lot of the “juke” music that’s coming out of Chicago, not all of it’s good, but if you like really fast “eye-vibrating” music then it does the job. I’ve just heard the Fhloston Paradigm, which is really good.

The Fiddleback: Can you describe your interest in junk food? What would you do if you woke up tomorrow and there were no more hot dogs?

JK: Junk food is mingin’ (disgusting), but often times I love it. But to go into a bit more depth—I’m interested by the strangeness of the whole culture of junk/ fast food. Like the way it’s presented and marketed to us, the TV commercials, the packaging, fast food restaurant architecture, the oddness of the interiors, the mechanical nature of the processed food industry—the eerie sort of “staged” formalities and routines that the poor employees or “team members” of fast food outlets are forced to participate in. I see it all as this bizarre sort of futuristic dystopian homogenisation of food, taste and eating.

Scotland is notorious for it’s junk-food culture. If you go to Scotland, you’ll just see people wandering around in the rain, eating fish n’ chips and deep-fried sausages out of newsprint. My Dad once saw a guy on his hands and knees eating a fish supper off the sidewalk! One time I dropped a deep-fried sausage, and within minutes somebody had grabbed it off of the sidewalk. But in America you have more of the big homogenous corporate chain restaurants. These interest me because they all have their unique forms of architecture.

Having said all of this, hotdogs are fucking righteous!

——–

Jamie Kinroy