An Interview with Matthew Dunn

by Benjamin Davis Brockman

by Benjamin Davis Brockman

August 1, 2012

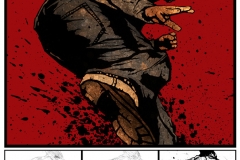

Matthew Dunn took the plunge into the world of full-time art four years ago. His lifelong passion for comics and illustrations led him to a prolific studio practice and the creation of graphic work for a broad range of outlets and applications. His work can be seen on t-shirts and posters for a number of creative ventures, as well gallery walls. Throughout his work, the central theme of the gas mask, and the emergence of a shadowy masked figure named Leroy, hint at the scope of a larger, unfolding narrative. In an online web-comic series he publishes himself through his website, Dunn has set the stage for the story of Leroy to come to life. Living in Brunswick, Australia, with his wife and two cats, Matthew works from home, producing ongoing web—comics, illustrations and designs.

I first discovered him through his design work for the immaculate double LP Mankind (The Crafty Ape) by post-rock super group, Crippled Black Phoenix. The bold graphic imagery that decorates that record is a perfect match for its content. Mankind (The Crafty Ape) is a dark, sprawling epic, and Dunn’s figures give color and shape to CPB’s three-act concept album as well as the band’s ongoing themes of hope amidst the calamities of our time. It’s no secret that the graphic novel is in its heyday—tackling adult themes and dark subject matter in a domain once ruled by Archie and Jughead. Just as this medium grows rapidly in scope, so does its role in a number of artistic venues outside the page and of gallery walls.

Here, Dunn has worked closely with Justin Greaves, CPB’s founder, in a rich collaborative expression across musical and visual media. He has provided work for posters, shirts and the lavish packaging of their limited edition live LP Poznan 2011 A.D. Similar collaborations of note might be what Gerald Scarfe did with Pink Floyd or Damon Albarn and Jamie Hewlitt’s Gorillaz. But the result here is far less pointed, allowing for the respective landscapes and soundscapes to hybridize, while drawing subtly from either creative well. I caught up with him to chat about this ongoing project and his many creative ventures.

The Fiddleback: How did you become involved with Crippled Black Phoenix? How would you describe that working relationship?

Matthew Dunn: I initially contacted them in relation to doing a CBP themed exhibition. Shortly after that Justin (Greaves) asked me to design a t-shirt for a tour they were about to embark on, and everything just snowballed from there. That was around the end of 2010. Since then I’ve had the exhibition, designed a stack of t-shirts, tour posters, and did all the art and design for two albums (with a third currently in the works).

The working relationship with Justin is pretty freewheeling. It generally involves late night calls where we end up spending less time planning things than we do just talking shit and having a laugh. Justin and I operate in a lot of similar creative territories as far as themes go, so everything happens quite naturally.

As far as the process goes, it varies with each project. Sometimes it’s just a case of me getting an email saying “We need a poster for …..” and me then putting something together for them to use. For the Mankind (The Crafty Ape) album, Justin sent me demos and notes on the songs, and I worked up a comic sequence for each track. And for the recent Poznan Live 2011 A.D. album, I worked closely with Todd from Clearview Records. The production values of the complete package grew beyond its initial scope, which is quite rare, and made it a very exciting experience.

The Fiddleback: Using the word “commercial” in a very loose, relative way, does working with other parties on commercial projects influence your creative practice? In other words, do you see design work and your personal work to be exclusive of each other in any way?

MD: I generally choose “commercial” projects that are related in some capacity to the types of themes that I explore in my own personal projects, so the divide between the two isn’t so great. Beyond that I’ll generally choose jobs that offer some creative challenge for me, be it in a design sense or just tackling a subject that I wouldn’t normally work on.

The Fiddleback: The gas mask may be the most prevalent motif occurring in your work. What does this represent to you symbolically, and what is its place in the overarching narrative of your art?

MD: The short answer is simply that I like drawing gas masks. The long answer is that the different masks and animal heads that appear regularly in my work are an ongoing experiment for me to find different ways to capture mood and emotion without having the usual facial expressions to express it. The gas mask for me, when you first see it, is soul—less and cold, but I find the more you stare at it the more it becomes imbued with emotion. For my character Leroy, who always wears a gas mask, it’s a way to hide from himself and the people around him. My lifelong love of comic books has also played a big part in that obsession and fascination with masks.

I think the advantage comics have over other mediums is that you’re able to take much bigger risks because you’re not dealing with a multimillion-dollar budget.

The Fiddleback: In your opinion, what is the current state of the graphic novel? Where do you see this art form heading, and how is that different than the way it has functioned historically?

MD: As far as creativity goes, I think the current era of comics is incredibly exciting and inspiring. The variety of titles available these days is so wide ranging, and there are a range of avenues for publishing/distribution, from the major publishers through to self-publishing. While superheroes are still a very dominant element of the comic world, there are more and more titles being released that reach far beyond that.

Thankfully the days of the popular “comics are for kids” mindset are mostly behind us, and the medium is given a lot more respect as an art form than it has in the past.

The Fiddleback: Who are your chief past and present influences? Who is working right now in music, film, art or otherwise, that excites you?

MD: As far as visual art is concerned, Mike Mignola and Dave McKean would be the two main artists who have had the longest ongoing influence on my own work. Mignola has a sense of mood and pacing in his comic work that is unmatched, and his approach to the design and composition of comic pages and covers is so unique. McKean’s art has a much more emotional and raw impact on me. He has a wide range of styles and approaches, but when you see his work you instantly recognize it as his own.

Beyond them I’m always inspired by the work of George Pratt, John Paul Leon, Gary Gianni, Ashley Wood, Duncan Fegredo, Jock, Kent Williams, Jason Shawn Alexander, Jeff Lemire, J.H. Williams, Henry Darger, Charles Schulz, George Herriman, Bill Sienkiewicz, Baron Storey, and many more.

With music, there’s CBP (obviously), Mark Lanegan, Sigur Ros, Daniel Johnston, Johnny Cash, The Black Heart Procession, Dirty Three, Silver Mt Zion, Tom Waits, The Flaming Lips, Mogwai, Bruce Peninsula, and many more. I play music constantly while I work; it can really help to get me in the right mood for whatever it is I’m currently working on.

Films that I watch regularly include The Road, The Devil’s Rejects, Pan’s Labyrinth, Dark Knight, The Devil And Daniel Johnston, Where The Wild Things Are, There Are Many Of Us, In The Realms Of The Unreal, and, again, many more. TV series such as The Wire and Deadwood are also good sources of inspiration.

The Fiddleback: I first discovered your work through the Crippled Black Phoenix Facebook page. What role does social media play for you?

MD: Social media is a valuable tool in regards to reaching people beyond those in your local area. It opens up a lot of doors in relation to making connections and sharing your work with a much larger audience. It can also be a bit of a trap that can steal away a lot of time, so I find in that regard I have to schedule my online activity to avoid getting too caught up in it all.

The Fiddleback: What do you think of this quote from Alan Moore? “There’s been a growing dissatisfaction and distrust with the conventional publishing industry, in that you tend to have a lot of formerly reputable imprints now owned by big conglomerates. As a result, there’s a growing number of professional writers now going to small presses, self-publishing, or trying other kinds of [distribution] strategies. The same is true of music and cinema. It seems that every movie is a remake of something that was better when it was first released in a foreign language, as a 1960s TV show, or even as a comic book. Now you’ve got theme park rides as the source material of movies. The only things left are breakfast cereal mascots. In our lifetime, we will see Johnny Depp playing Captain Crunch.”

MD: I think Moore’s statement certainly has relevance. There have been more big name creators shifting over to creator-owned publishing avenues as it provides a lot more freedom and ownership. But the line between mainstream and small press seems a bit more blurry than usual, with creators often working in both areas at the same time. (That’s nothing new, but it does seem to be happening more these days, which is great.) For example, one of my favorite mainstream comics at the moment is the DC title Animal Man, written by Jeff Lemire. Lemire has produced some of my favorite comics in recent years (such as Sweet Tooth and the Essex County Trilogy), and he’s able to bring his unique non-mainstream voice over to a very mainstream comic universe.

I think the advantage comics have over other mediums is that you’re able to take much bigger risks because you’re not dealing with a multimillion-dollar budget. So while the film industry may play it safe, the comic industry can experiment more, and as a result they’re able to try more original things with a greater sense of freedom.

The Fiddleback: You are currently publishing a new page of your graphic novel every two weeks via your website. What does the internet mean for the future of comics?

MD: It offers a wider range of options and control of your work. And with the popularity of the iPad and similar devices the whole world of webcomics now has increased relevance. Some people seem to think that there can only be printed or digital media, but I think each avenue offers different things and both formats will remain relevant. I’ve seen some fantastic digital comics, but at the same time nothing will ever compare to the wonderful feeling of holding a physical book in your hands. The internet has also made the concept of crowdsource funding more available, which makes self-publishing a much more realistic and manageable option.

The Fiddleback: How do you see the relationship between so-called “fine art” and “graphic art?” In other words, do you think there is a great distinction there? In what ways do you see that changing or not changing?

MD: I don’t think there’s as clear a distinction between such things these days. The labeling of art is always a tricky territory to venture into and is something I tend to avoid for the most part. Art is totally subjective, meaning different things to different people.

The Fiddleback: What are you working on currently?

MD: I’m currently preparing for a joint exhibition in September of this year (with a fantastic Melbourne artist, Kaitlin Beckett), as well as two new comics (the first of which should be available in August, and the second (featuring Leroy) being released later in the year). I also have a few collaborative projects at various stages of development, plus a few more art books slowly coming together. And, as always, there’s always something CBP-related floating around on my drawing table.

——–

Matthew Dunn